2. 华南国家植物园, 广州 510650;

3. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049;

4. 广东省科学院广州地理研究所, 广州 510070

2. South China National Botanical Garden, Guangzhou 510650, China;

3. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China;

4. Guangzhou Institute of Geography, Guangdong Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510070, China

随着我国社会和经济的快速发展,社会对于纸浆、木材等林木产品的需求日益增加。桉树(Eucalyptus)因其生长迅速、轮伐期短、环境适应性强以及当年营造即可当年成林等特点[1–2],得以在我国南方地区大面积种植[3]。然而当前社会在桉树人工林的经营过程中,往往只注重桉树经济上的效益,忽略了其生态效益[4],集约化桉树纯林大规模的构建引发了林下物种多样性减少、土壤质量严重退化、外来物种入侵加剧等一系列生态问题[3, 5]。为了缓解上述问题,提高桉树人工林质量及其生态系统服务功能,有关桉树纯林向近自然人工林改造以及桉树混交林构建的研究近年来逐渐受到关注。

研究表明,混交林在维持生物多样性和生态系统功能等方面发挥重要作用,例如增加生物量、提高生产力和碳封存[6–7],提高土壤肥力和促进养分循环[8–9],改善风险管理以防范病虫害[10–12],以及提升应对未来气候变化的能力[13–14]等。随着“close-to-nature forests”这一概念的提出,结合桉树早期的速生特性和乡土树种在维持生态系统稳定性方面的突出作用,通过营造桉树与乡土树种混交林对于提高林地生态服务功能、增强林地恢复力具有重要意义[4, 15–16]。因此,将桉树单一纯林改造成与乡土树种混交林是未来人工林发展的一个关键目标。

叶片性状是表征植物功能性状中重要的定量指标,与植物的资源(光照、养分和水)获取能力密切相关。随着资源有效性的变化,植物会在各叶片性状之间进行资源上的权衡以使其资源利用最大化,这就形成了植物在当前环境下的生态策略[17–18]。叶片性状之间的这种权衡关系决定了植物的行为和生产,因此被认为是树木生长的预测因子,其对环境变化的响应对于树木的生存和竞争至关重要[19–20]。在人工林的营造过程中,不同的混交树种和不同的混交模式均会影响物种间的相互作用和人工林的林分环境,进而影响资源有效性、土壤理化性质和微环境等[21–23]。因此,可以利用植物的叶片性状来预测不同树种混交和不同混交模式人工林的生产力和生态系统功能,这对于未来南亚热带多用途混交林的设计和物种选择具有重要的借鉴作用。

造林树种在混交林中的占比对于林分的生长和发育也有重要影响。当上层树种的比例过高时可能会抑制下层树种的生长发育,从而导致混交效果不佳[12]。汪清等[24]报道增加马尾松(Pinus massoniana)-木荷(Schima superba)混交林中马尾松的混交比例会导致林内的种内竞争强度增大。Santos等[9, 25]报道, 相比于巨尾桉(Eucalyptus urograndis)纯林,巨尾桉在其与马占相思(Acacia mangium)各占50%的混交林中具有更高的胸径和树高,并且在林分水平上具有更快的养分循环速率和更高的养分利用效率。这都表明合适的树种混交比例对于人工林的结构、动态和生产力至关重要[26]。目前有关各造林树种的资源利用效率(光、水和养分)如何响应混交比例的研究已有报道,但大多只是基于2树种的混交试验, 混交比例在多样性较高的混交林中的影响还鲜有报道。另一方面,有关混交比例影响树种叶片性状的研究也比较匮乏[27]。因此,本研究以南亚热带4种混交比例的桉树混交林和桉树纯林为对象,研究尾叶桉(Eucalyptus urophylla)和3种优势乡土树种华润楠(Machilus chinensis)、阴香(Cinnamomum burmannii)、灰木莲(Manglietia glauca)的叶片生理性状、结构性状和化学性状在不同混交比例的桉树-乡土树种混交林中的差异,探讨混交乡土树种及增加乡土树种占比对4树种资源利用策略的影响,为我国南亚热带生态恢复用途桉树混交林的乡土树种选择选种与设计提供科学依据与参考。

1 材料和方法 1.1 研究区概况研究区位于广东省鹤山市中国科学院鹤山丘陵综合开放试验站共和样地(112°54′ E,22°41′ N),该试验站是中国生态系统研究网络(Chinese Ecosystem Research Network,CERN)的核心台站之一。该地区为典型的南亚热带季风气候,干湿季分明,4月—9月为湿季,10月—次年3月为干季,年均温为21.7 ℃,最冷月平均温度为12.6 ℃,最热月平均温度为29.2 ℃。年均降水量约1 700 mm,多集中于雨季[28]。土壤为砖红壤。

本研究选取桉树纯林(Eucalyptus monoculture, EM)和4种混交比例的桉树-乡土树种人工林,混交林包括50%尾叶桉(E. urophylla, EU)+50%乡土树种(50%NS)、60%EU+40%NS、70%EU+30%NS和80% EU+20%NS。混交林中的起始乡土树种均为华润楠、阴香、灰木莲、秋枫(Bischofia javanica)、枫香(Liquidambar formosana)、观光木(Michelia odora)、五桠果(Dillenia indica)和蓝花楹(Jacaranda mimosifolia)。林下植被均以芒萁(Dicranopteris dichotoma)和乌毛蕨(Blechnum orientale)为主。

人工林均于2005年5月在退化的丘陵荒坡上建立,植株间距为3 m×2 m,混交林的混交方式为带状混交,采用完全随机设计进行人工林配置。每种人工林均设有3个重复样地,每个样地面积约1 hm2。此外,经过15 a的自然演替,不同混交比例人工林内乡土物种的生存状况存在较大差异,故本研究只选取了3种共有优势乡土树种作为研究对象:华润楠(MC)、阴香(CB)和灰木莲(MG)。华润楠、阴香、灰木莲和尾叶桉的平均树高分别为8.4、7.8、10.9和14.9 m,平均胸径分别为13.29、10.65、12.53和17.30 cm (表 1)。

| 表 1 桉树-乡土树种混交林样地概况 Table 1 Plot profile of mixed plantations of Eucalyptus urophylla and native species |

在每个人工林样地中,每种目标树种选取4~5株大小、长势接近且生长良好的植株进行取样并标记。于2020年11月(干季)和2021年7月分别从样株树冠中上部采集成熟叶片,放入聚乙烯袋中密封以保持水分,在实验室中进行相关指标的测定。采用LI-3000C叶面积仪(LI-COR, USA)测定成熟叶片面积(leaf area, LA),记录除去叶柄后的叶片鲜重(leaf fresh weight, LFW)。然后,将叶片置于65 ℃下烘72 h, 测定叶片干重(leaf dry weight, LDW),并计算比叶面积(specific leaf area, SLA)、比叶质量(leaf mass per area, LMA)和叶干物质含量(leaf dry matter content, LDMC)。SLA=LA/LDW; LMA=LDW/ LA; LDMC=LDW/LFW。将烘干的叶片粉碎并过60目筛,分别采用半微量凯氏定氮法和钼锑抗比色法测定成熟叶片的氮(N)和磷(P)浓度[29]。

利用LI-6800光合系统(LI-COR, USA)测定成熟叶片的生理性状。分别于2021年8月(湿季)和2022年1月(干季)上午的8:00–12:00对每株样株至少6片阳生叶进行单位面积最大光合速率(maximum photosynthetic rate per unit of leaf area, Aarea)、蒸腾速率(transpiration rate per unit of leaf area, Tarea)和水分利用效率(water use efficiency, WUE)的测定。测定时光合有效辐射为1 500 μmol/(m2·s),叶室温度设定为25 ℃,利用CO2钢瓶设定参比室CO2通量为400 μmol/mol。WUE=Aarea/Tarea,单位叶片质量的最大光合速率(Amass)=Aarea/LMA, 单位叶片质量的蒸腾速率(Tmass)=Tarea/LMA[30]。此外,叶片的光合氮利用效率(photosynthetic nitrogen use efficiency, PNUE)= Amass/Nmass, 光合磷利用效率(photosynthetic phosphorus use efficiency, PPUE)=Tmass/Pmass[31]。

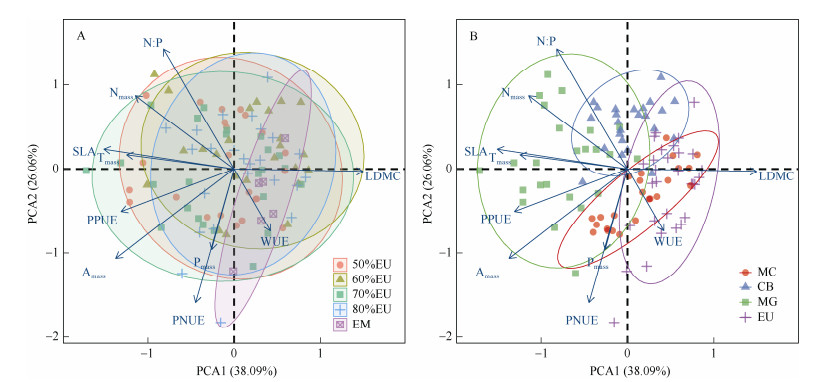

1.3 数据的统计分析统计分析前,对所有数据进行了正态检验和方差同质性检验,并在分析前对不符合条件的数据进行了log10转换。利用三因素方差分析方法(ANOVA)分析季节、物种和混交比例及其交互作用对各叶片性状的影响,并用最小差异显著法(LSD)进行事后多重比较(显著水平设置为P < 0.05)。主成分分析(PCA)用于分析各叶片性状在不同比例桉树混交林和不同造林树种中的总体差异。所有的数据分析与作图均使用R统计软件(V 4.0.3)完成。

2 结果和分析 2.1 叶片结构和化学性状比较结果表明,不同混交比例下4种优势树种的叶片结构和化学性状存在显著的种间差异(表 2)。灰木莲的平均SLA、Nmass、Pmass最高,阴香的N׃P最高,尾叶桉的LDMC最高(图 1)。SLA、Nmass和Pmass在干湿季均存在较大差异,其中SLA在湿季较高,Nmass在干季较高,Pmass和N: P受干湿季的影响因物种而异。整体上,SLA和Nmass受混交比例主效应的影响显著,LDMC和Pmass随桉树混交比例的变化因物种而异,混交比例对N: P没有显著影响。但在物种层面上,除灰木莲的Nmass和华润楠在干季的Pmass随桉树混交比例的增加而降低外,其余树种的SLA、LDMC、Nmass和Pmass随桉树混交比例的增加无显著变化。

| 表 2 季节、物种、混交比例及其交互作用对叶片性状的影响 Table 2 Effects of season, species, mixed proportions and their interactions on leaf traits |

|

图 1 不同混交比例下4树种在干季和湿季的叶片性状比较。柱上不同字母表示差异显著(P < 0.05)。 Fig. 1 Comparison of leaf traits of four tree species in dry season and wet season under different mixed proportions. Different letters upon column indicate significant differences at 0.05 level. |

4优势树种的叶片生理性状存在显著的种间差异(表 2)。灰木莲的Tmass和PPUE最高,阴香的Amass最高、PNUE和Tarea最低,尾叶桉的Aarea最高(图 2)。4树种的WUE没有显著的种间差异。叶片生理性状受干湿季的影响较大,其中Tarea、Tmass和PPUE表现为湿季高于干季,WUE表现为干季高于湿季, Aarea、Amass和PNUE受干湿季的影响因物种而异。混交比例整体上对Aarea、Amass、Tmass和PNUE存在显著影响,对Tarea的影响因物种而异。但是在物种层面上,只有阴香的Aarea、Amass、PNUE和PPUE在干季随着桉树混交比例的增加呈降低的趋势,其余物种的叶片生理性状大多随桉树混交比例的增加变化不明显。

|

图 2 不同混交比例下4树种在干季和湿季的叶片生理性状比较 Fig. 2 Comparison of leaf physiological traits of four tree species in dry season and wet season under different mixed proportions |

主成分分析结果表明(图 3),第一主轴和第二主轴对总方差的解释度分别为38.09%和26.06%。与尾叶桉纯林相比,4种混交林均表现出了更高的SLA、N׃P、Amass、Tmass、PPUE和Nmass (图 3: A),其中70%EU具有最高的SLA、PPUE、Tmass和Amass。当以4树种作为分组时,与尾叶桉相比,乡土树种则具有更高的SLA、N׃P、Amass、Tmass、PPUE和Nmass (图 3: B)。此外,除华润楠和阴香的WUE和LDMC等叶片性状与尾叶桉存在部分重合之外,4树种的其他叶片物理、化学和生理性状出现了明显的分化与互补(图 3: B)。

|

图 3 不同混交比例优势树种叶片性状的主成分分析。A: 混交比例; B: 树种。 Fig. 3 Principal component analysis of leaf traits of dominant tree species under different mixed proportions. A: Mixed proportion; B: Species. |

本研究结果表明,4造林树种中,以灰木莲的SLA、PPUE、Amass、Tmass和叶片养分含量最高。根据经典的“叶经济谱”理论[32],灰木莲倾向于采取资源获取型的生态策略。尾叶桉的SLA、Amass、Tmass、叶片养分含量最低,说明尾叶桉倾向于采取保守型的生态策略。然而,低SLA通常对应较低的相对生长速率[33–34],本研究中相同树龄的尾叶桉植株平均大小(高度和胸径分别为14.9 m和17.3 cm)明显高于乡土树种,说明尾叶桉的相对生长速率和生物量更高,这与其较低的SLA相矛盾。有研究表明,SLA与相对生长速率之间的关系会受植株大小的影响[35]。随着植物大小的增加,出于对机械和液压的支撑,通常会导致植物的叶片生物量在总生物量中所占比重大幅减少,进而越来越多的总生物量会被用于构建和维护支撑组织[36–37]。换言之,尾叶桉较高的相对生长率主要体现在对树干部分生物量的投资,其对于叶片生物量的投资较少。因此, 本研究结果支持了Giber等[35]的观点,即SLA这一指标对相对生长速率的预测效果可能受植物个体发育的显著影响。另一方面,尾叶桉具有较高的PNUE,这与尾叶桉较高的相对生长速率相对应。因此我们认为,尾叶桉结合了采取资源获取型策略的快速生长型物种和适应养分贫乏环境的保守型物种的典型特征。Richards等[38]对澳大利亚山银桦(Grevillea robusta)人工林的研究中也观察到了类似现象。此外,高LDMC的叶片往往更加坚韧[39], 较高的LDMC可能有助于尾叶桉顶端的叶片抵御外界的物理灾害(研究区域主要为台风)。

桉树是人工林资源强有力的竞争者,通常受益于混交林中树种的混合效应并抑制混交林中其他树木的生长[40–41]。然而在本研究中,4造林树种的叶片结构、化学和生理性状受树种混交比例的影响较小,除灰木莲的Nmass、华润楠的Pmass以及阴香在干季的Amass和PNUE随尾叶桉混交比例增加有降低的趋势以外,4树种的叶片性状随乡土树种混交比例增加的变化并不具有统计学意义上的差异, Amazonas等[42]在巴西的桉树与乡土树种的混交试验中也发现了类似的现象。这一方面可能是因为尾叶桉与乡土树种之间已经出现了树冠分层,上层树冠中尾叶桉的快速生长导致不同混交比例的乡土树种冠层的光环境比较接近,所以目标树种对光资源的获取能力受混交比例的影响不大[12]。另一方面,这可能与当地强烈的磷限制有关。本研究中的试验样地土壤有效磷含量极低(平均小于0.5 mg/kg[43], 并且4个造林树种的叶片N׃P均明显高于目前普遍认为的磷限制阈值(N׃P > 16[44]),强烈的磷限制会导致植物-土壤系统元素化学计量的失衡,从而导致植物的功能和生长受到很大的限制[45–46],可能掩盖了树种混交效应对植物叶片性状的影响[47]。此外,本研究中的混交林乡土树种种植条带具有较高的多样性(6~8种乡土种),由于乡土树种之间并没有出现明显的树冠分层,他们对于光照的强烈竞争可能会导致目标树种受到多样化的邻体影响[41],这可能解释了3种乡土树种部分叶片性状随尾叶桉混交比例增加的复杂变化(增加或不规律)。

本研究中,除了WUE和LDMC,4优势树种的其他叶片性状均出现了明显的分化与互补,尤其是乡土树种灰木莲与尾叶桉在SLA、N׃P、Amass、Tmass、PPUE和Nmass等性状上几乎没有任何的重叠。与人工纯林相比,组成物种的营养特征和资源利用的互补性是混交林稳定性和生产力更高的主要原因之一[48–49]。本研究中灰木莲和尾叶桉之间的叶片资源利用高度互补,两者之间对于资源的竞争减弱,因此我们认为灰木莲可能是与尾叶桉混交的理想树种。从林分尺度上看,我们发现桉树-乡土树种混交林的SLA和光合能力在林分水平上显著高于尾叶桉纯林,这种提升的幅度以70%EU最高。这说明混交乡土树种可以提高林分整体的光捕获能力,对于提高林分生产力可能有积极的影响。然而,混交林在林分水平的叶片N: P也显著高于尾叶桉纯林,这说明混交林虽然成功地促进了树木生长和林分生产力,但这可能也意味着磷限制的加剧。换言之,强烈的磷限制可能会抑制混交林中正向的混交效应,从而导致混交林的造林效果不佳。因此我们建议,在未来南亚热带桉树人工林的构建与改造中,一方面应着重挑选与桉树资源利用互补的乡土树种,另一方面应挑选一些能够优化混交林磷素循环利用的树种,如能够有效的从土壤惰性磷库中获取磷的树种[50]。

综上,桉树-乡土树种混交林中4优势造林树种的叶片性状存在明显的种间差异,其中灰木莲倾向于采取资源获取型的生态策略,尾叶桉则是兼顾了资源获取型和保守型的物种特征。物种水平上,灰木莲与尾叶桉之间的叶片资源利用高度互补,可能是与尾叶桉混交的理想树种,但是树种混交比例对于4造林树种的叶片结构、化学和生理性状影响不大。林分水平上,桉树与乡土树种混交能够提高林分的光捕获和光合能力,但也加剧了植物生长的磷限制。在未来南亚热带桉树人工林的构建与改造中,应优先挑选与桉树资源利用互补并优化混交林磷素循环利用的乡土树种。

| [1] |

PBOYLE J R, WINJUM J K, KAVANAGH K, et al. Planted Forests: Contributions to the Quest for Sustainable Societies[M]. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1999.

|

| [2] |

LUO S M, HE D J, XIE Y L, et al. Effect of stand density on community structure and ecological effect of Eucalyptus urophylta×E. eamalducensis plantation[J]. J Trop Subtrop Bot, 2010, 18(4): 357-363. 罗素梅, 何东进, 谢益林, 等. 林分密度对尾赤桉人工林群落结构与生态效应的影响研究[J]. 热带亚热带植物学报, 2010, 18(4): 357-363. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-3395.2010.04.003 |

| [3] |

WILLIAMS R A. Mitigating biodiversity concerns in Eucalyptus plantations located in south China[J]. J Biosci Med, 2015, 3(6): 1-8. DOI:10.4236/jbm.2015.36001 |

| [4] |

BRANCALION P H S, AMAZONAS N T, CHAZDON R L, et al. Exotic eucalypts: From demonized trees to allies of tropical forest restoration?[J]. J Appl Ecol, 2020, 57(1): 55-66. DOI:10.1111/1365-2664.13513 |

| [5] |

ZHOU X G, ZHU H G, WEN Y G, et al. Intensive management and declines in soil nutrients lead to serious exotic plant invasion in Eucalyptus plantations under successive short-rotation regimes[J]. Land Degrad Dev, 2020, 31(3): 297-310. DOI:10.1002/ldr.3449 |

| [6] |

BAUHUS J, VAN WINDEN A P, NICOTRA A B. Aboveground interactions and productivity in mixed-species plantations of Acacia mearnsii and Eucalyptus globulus[J]. Can J For Res, 2004, 34(3): 686-694. DOI:10.1139/X03-243 |

| [7] |

ZHANG H, GUAN D S, SONG M W. Biomass and carbon storage of Eucalyptus and Acacia plantations in the Pearl River Delta, south China[J]. For Ecol Manage, 2012, 277: 90-97. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2012.04.016 |

| [8] |

FORRESTER D I, BAUHUS J, COWIE A L. Nutrient cycling in a mixed-species plantation of Eucalyptus globulus and Acacia mearnsii[J]. Can J For Res, 2005, 35(12): 2942-2950. DOI:10.1139/X05-214 |

| [9] |

SANTOS F M, CHAER G M, DINIZ A R, et al. Nutrient cycling over five years of mixed-species plantations of Eucalyptus and Acacia on a sandy tropical soil[J]. For Ecol Manage, 2017, 384: 110-121. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2016.10.041 |

| [10] |

MONTAGNINI F. Accumulation in above-ground biomass and soil storage of mineral nutrients in pure and mixed plantations in a humid tropical lowland[J]. For Ecol Manage, 2000, 134(1-3): 257-270. DOI:10.1016/S0378-1127(99)00262-5 |

| [11] |

SCHERER-LORENZEN M, KÖRNER C, SCHULZE E D. Forest Diversity and Function: Temperate and Boreal Systems[M]. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2005.

|

| [12] |

KELTY M J. The role of species mixtures in plantation forestry[J]. For Ecol Manage, 2006, 233(2/3): 195-204. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2006.05.011 |

| [13] |

MILLAR C I, STEPHENSON N L, STEPHENS S L, et al. Climate change and forests of the future: Managing in the face of uncertainty[J]. Ecol Appl, 2007, 17(8): 2145-2151. DOI:10.1890/06-1715.1 |

| [14] |

FELTON A, NILSSON U, SONESSON J, et al. Replacing monocultures with mixed-species stands: Ecosystem service implications of two production forest alternatives in Sweden[J]. Ambio, 2016, 45(2): 124-139. DOI:10.1007/s13280-015-0749-2 |

| [15] |

LARSEN J B, NIELSEN A B. Nature-based forest management: Where are we going? Elaborating forest development types in and with practice[J]. For Ecol Manage, 2007, 238(1/2/3): 107-117. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2006.09.087 |

| [16] |

AMAZONAS N T, FORRESTER D I, OLIVEIRA R S, et al. Combining Eucalyptus wood production with the recovery of native tree diversity in mixed plantings: Implications for water use and availability[J]. For Ecol Manage, 2018, 418: 34-40. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2017.12.006 |

| [17] |

REICH P B. The world-wide 'fast-slow' plant economics spectrum: A traits manifesto[J]. J Ecol, 2014, 102(2): 275-301. DOI:10.1111/1365-2745.12211 |

| [18] |

LIU X J, MA K P. Plant functional traits-concepts, applications and future directions[J]. Sci Sin Vitae, 2015, 45(4): 325-339. 刘晓娟, 马克平. 植物功能性状研究进展[J]. 中国科学: 生命科学, 2015, 45(4): 325-339. DOI:10.1360/N052014-00244 |

| [19] |

MCDOWELL N, ALLEN C D, ANDERSON-TEIXEIRA K, et al. Drivers and mechanisms of tree mortality in moist tropical forests[J]. New Phytol, 2018, 219(3): 851-869. DOI:10.1111/nph.15027 |

| [20] |

KUNSTLER G, FALSTER D, COOMES D A, et al. Plant functional traits have globally consistent effects on competition[J]. Nature, 2016, 529(7585): 204-207. DOI:10.1038/nature16476 |

| [21] |

ROA-FUENTES L L, TEMPLER P H, CAMPO J. Effects of precipitation regime and soil nitrogen on leaf traits in seasonally dry tropical forests of the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico[J]. Oecologia, 2015, 179(2): 585-597. DOI:10.1007/s00442-015-3354-y |

| [22] |

CHEN C, CHEN H Y H, CHEN X L. Functional diversity enhances, but exploitative traits reduce tree mixture effects on microbial biomass[J]. Funct Ecol, 2020, 34(1): 276-286. DOI:10.1111/1365-2435.13459 |

| [23] |

ROSENFIELD M V, KELLER J K, CLAUSEN C, et al. Leaf traits can be used to predict rates of litter decomposition[J]. Oikos, 2020, 129(10): 1589-1596. DOI:10.1111/oik.06470 |

| [24] |

WANG Q, PAN P, OUYANG X Z, et al. Intraspecific and interspecific competition intensity in mixed plantation with different proportion of Pinus massoniana and Schima superba[J]. Chin J Ecol, 2021, 40(1): 49-57. 汪清, 潘萍, 欧阳勋志, 等. 马尾松-木荷不同比例混交林种内和种间竞争强度[J]. 生态学杂志, 2021, 40(1): 49-57. DOI:10.13292/j.1000-4890.202101.016 |

| [25] |

SANTOS, MARTINI F, BALIEIRO, et al. Dynamics of aboveground biomass accumulation in monospecific and mixed-species plantations of Eucalyptus and Acacia on a Brazilian sandy soil[J]. For Ecol Manage, 2016, 363: 86-97. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2015.12.028 |

| [26] |

DEL RÍO, PRETZSCH M, ALBERDI H, et al. Characterization of the structure, dynamics, and productivity of mixed-species stands: Review and perspectives[J]. Eur J For Res, 2016, 135(1): 23-49. DOI:10.1007/s10342-015-0927-6 |

| [27] |

ZHA M Q, CHENG X R, YU M K, et al. Effects of mixing proportion on functional traits of Cunninghumia lanceolata and Zelkova schneideriana seedling[J]. Acta Ecol Sin, 2021, 41(21): 8556-8567. 查美琴, 成向荣, 虞木奎, 等. 不同混交比例对杉木和大叶榉幼苗功能性状的影响[J]. 生态学报, 2021, 41(21): 8556-8567. DOI:10.5846/stxb202007311999 |

| [28] |

WANG J, REN H, YANG L, et al. Establishment and early growth of introduced indigenous tree species in typical plantations and shrubland in south China[J]. For Ecol Manage, 2009, 258(7): 1293-1300. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2009.06.022 |

| [29] |

DONG M. Survey, Observation and Analysis of Terrestrial Biocommunities[M]. Beijing: Standards Press of China, 1997. 董鸣. 陆地生物群落调查观测与分析[M]. 北京: 中国标准出版社, 1997. |

| [30] |

HAN T T, REN H, WANG J, et al. Variations of leaf eco-physiological traits in relation to environmental factors during forest succession[J]. Ecol Indic, 2020, 117: 106511. DOI:10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106511 |

| [31] |

WRIGHT I J, REICH P B, CORNELISSEN J H C, et al. Assessing the generality of global leaf trait relationships[J]. New Phytol, 2005, 166(2): 485-496. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01349.x |

| [32] |

WRIGHT I J, REICH P B, WESTOBY M, et al. The worldwide leaf economics spectrum[J]. Nature, 2004, 428(6985): 821-827. DOI:10.1038/nature02403 |

| [33] |

POORTER L, WRIGHT S J, PAZ H, et al. Are functional traits good predictors of demographic rates? Evidence from five neotropical forests[J]. Ecology, 2008, 89(7): 1908-1920. DOI:10.1890/07-0207.1 |

| [34] |

PAINE C E T, AMISSAH L, AUGE H, et al. Globally, functional traits are weak predictors of juvenile tree growth, and we do not know why[J]. J Ecol, 2015, 103(4): 978-989. DOI:10.1111/1365-2745.12401 |

| [35] |

GIBERT A, GRAY E F, WESTOBY M, et al. On the link between functional traits and growth rate: Meta-analysis shows effects change with plant size, as predicted[J]. J Ecol, 2016, 104(5): 1488-1503. DOI:10.1111/1365-2745.12594 |

| [36] |

GIVNISH T J. Plant stems: Biomechanical adaptation for energy capture and influence on species distributions[M]// GARTNER B L. Plant Stems Physiology and Functional Morphology. San Diego: Academic Press, 1995.

|

| [37] |

KING D A. Size-related changes in tree proportions and their potential influence on the course of height growth[M]// MEINZER F C, LACHENBRUCH B, DAWSON T E. Size- and Age-Related Changes in Tree Structure and Function. Dordrecht: Springer, 2011.

|

| [38] |

RICHARDS A E, FORRESTER D I, BAUHUS J, et al. The influence of mixed tree plantations on the nutrition of individual species: A review[J]. Tree Physiol, 2010, 30(9): 1192-1208. DOI:10.1093/treephys/tpq035 |

| [39] |

PÉREZ-HARGUINDEGUY N, DÍAZ S, GARNIER E, et al. New handbook for standardised measurement of plant functional traits worldwide[J]. Aust J Bot, 2013, 61(3): 167-234. DOI:10.1071/BT12225 |

| [40] |

FORRESTER D I, BAUHUS J, COWIE A L, et al. Mixed-species plantations of Eucalyptus with nitrogen-fixing trees: A review[J]. For Ecol Manage, 2006, 233(2/3): 211-230. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2006.05.012 |

| [41] |

AMAZONAS N T, FORRESTER D I, SILVA C C, et al. High diversity mixed plantations of Eucalyptus and native trees: An interface between production and restoration for the tropics[J]. For Ecol Manage, 2018, 417: 247-256. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2018.03.015 |

| [42] |

AMAZONAS N T, FORRESTER D I, SILVA C C, et al. Light- and nutrient-related relationships in mixed plantations of Eucalyptus and a high diversity of native tree species[J]. New For, 2021, 52(5): 807-828. DOI:10.1007/s11056-020-09826-x |

| [43] |

LONG J. Evaluation of leaf nutrient resorption efficiency under mixed Eucalyptus and native trees plantations with different established proportions[D]. Beijing: University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2022. 龙靖. 不同比例桉树-乡土树种混交林叶片养分再吸收效率评价[D]. 北京: 中国科学院大学, 2022. |

| [44] |

KOERSELMAN W, MEULEMAN A F M. The vegetation N: P ratio: A new tool to detect the nature of nutrient limitation[J]. J Appl Ecol, 1996, 33(6): 1441-1450. DOI:10.2307/2404783 |

| [45] |

CAMPO J, GALLARDO J F, HERNÁNDEZ G. Leaf and litter nitrogen and phosphorus in three forests with low P supply[J]. Eur J For Res, 2014, 133(1): 121-129. DOI:10.1007/s10342-013-0748-4 |

| [46] |

YAN K, DUAN C Q, FU D G, et al. Leaf nitrogen and phosphorus stoichiometry of plant communities in geochemically phosphorusenriched soils in a subtropical mountainous region, SW China[J]. Environ Earth Sci, 2015, 74(5): 3867-3876. DOI:10.1007/s12665-015-4519-z |

| [47] |

LI M, HUANG C H, YANG T X, et al. Role of plant species and soil phosphorus concentrations in determining phosphorus: Nutrient stoichiometry in leaves and fine roots[J]. Plant Soil, 2019, 445(1/2): 231-242. DOI:10.1007/s11104-019-04288-3 |

| [48] |

HOOPER D U, CHAPIN F S, EWEL J J, et al. Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: A consensus of current knowledge[J]. Ecol Monogr, 2005, 75(1): 3-35. DOI:10.1890/04-0922 |

| [49] |

FORRESTER D I, BAUHUS J. A review of processes behind diversity-productivity relationships in forests[J]. Curr For Rep, 2016, 2(1): 45-61. DOI:10.1007/s40725-016-0031-2 |

| [50] |

SIDDIQUE I, ENGEL V L, PARROTTA J A, et al. Dominance of legume trees alters nutrient relations in mixed species forest restoration plantings within seven years[J]. Biogeochemistry, 2008, 88(1): 89-101. DOI:10.1007/s10533-008-9196-5 |

2024, Vol. 32

2024, Vol. 32