2. 华南国家植物园, 广州 510650;

3. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049

2. South China National Botanical Garden, Guangzhou 510650, China;

3. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

光不仅是植物光合作用的能量来源,也是调节植物生长发育重要的环境信号因子。在长期的进化过程中,植物形成了极为精细和完善的光感受和信号转导系统。光受体是植物识别和感受光的重要因子。在感知环境中光的强度、方向和光周期变化后,光受体发生定位、翻译后修饰和蛋白水平等生化特性的改变,通过光信号转导途径调控光响应基因的表达,并最终调节植物的生长发育过程[1]。目前, 已经鉴定报道的植物光受体有5类:感受红光(620~700 nm)和远红光(700~800 nm)的光敏色素(phytochromes, PHYs),感受蓝光和UV-A区(320~380 nm)的隐花色素(cryptochromes, CYRs),感受蓝光(380~500 nm)的向光素(phototropins, PHOTs),感受蓝绿光(450~520 nm)的ZTLs (zeitlupes)类蛋白,以及感受紫外光UV-B区(280~320 nm)的紫外光受体(UV RESISTANCE LOCUS 8, UVR8)[2]。不同类型的光受体调控了植物从种子萌发、幼苗形态建成、茎的伸长直至开花结实的整个生命周期过程[3]。

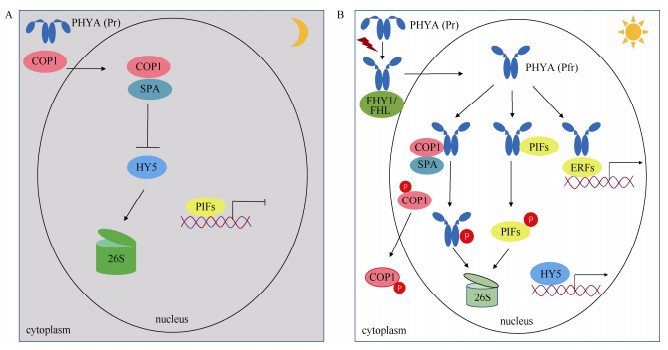

作为植物中唯一的远红光受体,光敏色素A (PHYA)具有区别于其他光受体的特性,如幼苗从黑暗转入照光后,PHYA快速的从细胞质穿梭至细胞核并被降解[4–6]。PHYA在进入细胞核后,通过调控关键转录因子如HY5 (elongated hypocotyl 5)和PIFs (phytochrome interacting factors)等蛋白稳定性来调节光响应基因的表达;另一方面,PHYA也直接结合到下游光响应基因的启动子区域,并促进或抑制其基因的表达[7–9]。

蛋白质翻译后修饰(post-translational modifications, PTMs)能调节蛋白质定位、结构、活性、互作以及生物学功能等,是真核生物生命活动的重要调节方式,其中常见的有磷酸化、泛素化、甲基化、酰基化和糖基化等[10]。大量的研究表明,磷酸化和泛素化等修饰在调节植物光受体生化特性和光信号转导途径中发挥重要的作用。如光照诱导的磷酸化修饰影响PHYA在细胞中的定位和功能[4, 11],而泛素化修饰则引起PHYA的降解[12–13];同时,光诱导的磷酸化修饰增强了隐花色素CRY1/CYR2以及向光素PHOT1的激酶活性[14–16]。

本文主要综述了近年来对光敏色素重要成员——PHYA介导光响应基因表达的作用机制,以及蛋白质翻译后修饰调节PHYA特性方面的研究进展,以期为利用光照提高农作物的产量和品质的分子育种提供理论参考。

1 光敏色素成员及结构特征拟南芥基因组编码5个光敏色素家族成员: PHYA、PHYB、PHYC、PHYD和PHYE,其中PHYA和PHYB为最主要的光敏色素。PHYA主要感知远红光(700~750 nm),而PHYB则主要感知红光(600~700 nm)。根据光敏色素在光下的稳定性,通常将其分为光稳定类型和光不稳定类型,其中仅PHYA为光不稳定类型的光敏色素[17]。光敏色素存在2种可逆的活性形式,即:在黑暗中吸收远红光后的非活性的红光吸收形式(Pr),该形式定位于细胞质中,性质稳定不易降解;另一种为吸收红光后的具有活性的远红光吸收形式(Pfr)[18–22]。

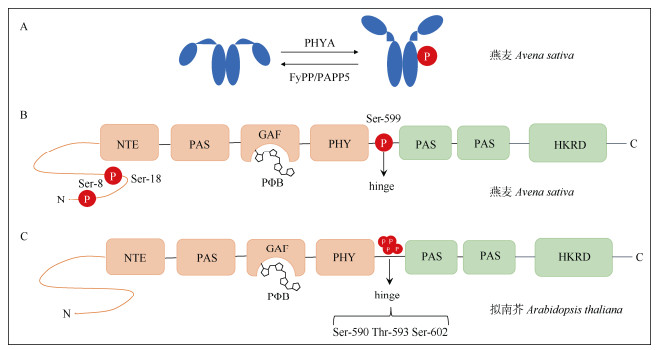

光敏色素在细胞质内以脱辅基的形式合成。脱辅基的光敏色素蛋白不能接收光子,在通过自催化共价结合四吡咯环色素小分子(PΦB)后,能够组装成具有完整生物学功能的光敏色素全蛋白[21, 23]。植物光敏色素成员均具有类似的结构域。在蛋白结构上,PHYA可分为氨基端(N端)的光信号感受区和羧基端(C端)的光信号传递区域,中间由灵活的铰链区相连接(图 1)。N端区域包括N端延伸区(NTE)、PAS、GAF和PHY等结构域,主要负责信号的输入;C端区域含有2个PAS的PAS相关结构域(PRD)以及组氨酸激酶(HKRD)相关结构域,主要负责调控、二聚化和信号的输出功能[18];铰链区则可能在光敏色素Pr与Pfr形式相互转换的过程中具有关键调控作用[4]。

|

图 1 PHYA蛋白的结构域 Fig. 1 Domains of PHYA protein |

在拟南芥中,PHYA的突变体在持续白光和红光下表现为野生型的光形态建成的表型,而在持续远红光下则表现为暗形态建成的表型,说明PHYA主要负责远红光信号的感知与传递[24–26]。在持续蓝光下,PHYA突变体也表现为长下胚轴的表型,表明PHYA也参与蓝光信号的感受与响应[27–28]。

前人研究表明,在黑暗条件下,PHYA蛋白定位于细胞质中;在感受光信号后,PHYA发生结构变化,在FHY/FHL蛋白的辅助下进入细胞核[29]。研究表明,PHYA通过多种途径参与调控光响应基因的表达。首先,入核的PHYA与一组特殊的bHLH (basic helix-loop-helix)类型的转录因子发生直接相互作用。这类与PHYA及其它光敏色素互作的转录因子被称为光敏色素互作因子(PIFs),包含有多个成员,PIF1~PIF8,这类蛋白为植物光形态建成的抑制因子[30–36]。PIFs类蛋白具有直接结合光响应基因启动子区域的G-box (CACGTG)顺式作用元件并调控其表达的活性。PHYA与PIFs蛋白互作,诱导其发生磷酸化并最终被泛素化途径降解,进而间接的调节植物光响应基因表达[30](图 2)。

|

图 2 PHYA调控光响应基因表达的作用模式。A: 黑暗条件;B: 照光条件。 Fig. 2 Action model of PHYA regulating light responsive gene expression. A: Dark condition; B: Light condition. |

其次,研究表明PHYA也能通过调控COP1 (constitutive photomorphogenic 1, COP1)与SPA (suppressor of phytochrome A)组成的蛋白复合体调节光响应基因表达。COP1为一种E3泛素连接酶,是植物光信号转导的主效抑制因子[37–40]。亚细胞定位研究显示,在黑暗生长的幼苗中COP1定位于细胞核;而当幼苗转入光照后COP1穿梭至细胞质中[41]。在黑暗下,COP1/SPA复合体与关键的光信号途径转录因子发生蛋白互作, 如HY5、HYH (HY5 homolog)、FHY3 (far-red elongated hypocotyls 3)、HFR1 (long hypocotyl in far-red 1)、FAR1 (far-red impaired response 1)和LAF1 (long after far-red light 1)等,并引起这些转录因子发生泛素化降解,从而抑制植物的光形态建成[42–47]。当植物转入照光后,PHYA进入细胞核,与COP1/SPA复合体发生蛋白互作,诱导COP1蛋白出核,抑制其形成有功能的E3泛素连接酶复合体,从而释放了各种转录因子的活性并启动大量光响应基因的表达[48];同时,COP1/SPA复合体也引起PHYA蛋白发生泛素化修饰,并最终被降解(图 3)。

|

图 3 PHYA蛋白多个位点发生磷酸化修饰。A: 燕麦PHYA自磷酸化以及被FyPP/PAPP5去磷酸化; B: 燕麦PHYA上3个位点发生磷酸化; C: 拟南芥PHYA的hinge区域3个位点发生磷酸化。 Fig. 3 PHYA protein are phosphorylated at multiple sites. A. Oats (Avena sativa) PHYA is auto-phosphorylated and dephosphorylated by FyPP/PAPP5; B. Three sites in oats PHYA are phosphorylated; C. Three sites in the hinge region of Arabidopsis PHYA are phosphorylated. |

此外,前人通过高通量染色质免疫共沉淀测序检测, 认为PHYA可以结合到大量光响应基因的启动子区域,表明PHYA可能不依赖下游PIFs转录因子的形式,而是直接参与调控了光响应基因的表达[9] (图 2)。最近的研究表明,光激活的PHYA和PHYB与转录因子ERF55和ERF58的DNA结合结构域互作,通过阻止它们与靶基因的结合,从而调控光依赖的种子萌发途径[49]。这些研究充分表明, PHYA以多种复杂的调控途径介导了植物光信号的转导以及光响应基因的表达。

3 PHYA蛋白的翻译后修饰及调控作用蛋白质是执行细胞功能的基本单元,通常在表达后还需要经过不同程度的翻译后修饰才能发挥生物学功能。近年来的研究表明,多种翻译后修饰,如磷酸化和泛素化修饰等在参与调节PHYA活性、稳定性以及生物学功能方面发挥了重要的作用[4, 11, 50–61]。

3.1 磷酸化修饰在生物体内,磷酸化是蛋白翻译后修饰中最为广泛的共价修饰形式,同时也是原核生物和真核生物中最重要的调控修饰形式,对蛋白质功能的正常发挥起着重要的调节作用[62]。蛋白的磷酸化修饰是指不同类型的蛋白质激酶(kinase)将ATP或GTP的γ位磷酸基团转移到底物蛋白质的氨基酸残基上, 如丝氨酸(serine, Ser)、苏氨酸(threonine, Thr)和酪氨酸(tyrosine, Tyr)位点上,而其逆向过程则是由多种蛋白质磷酸酶(phosphatase)催化调控。

早期对燕麦的研究表明,黑暗生长的燕麦幼苗体内的PHYA发生磷酸化修饰,后续利用纯化的PHYA蛋白进行鉴定,发现磷酸化的位点位于NTE区的Ser-8和Ser-18以及铰链区的Ser-599号位点上(图 3)[50]。对这些磷酸化修饰位点的功能分析表明,铰链区Ser-599号位点的磷酸化阻止了燕麦PHYA与其下游信号元件(如NDPK2)的相互作用[51],而NTE区的Ser到Ala (丙氨酸)模拟去磷酸化突变则能增加PHYA蛋白的稳定性和生物活性[52–54]。研究表明, 除燕麦PHYA对Ser-8和Ser-18位点能进行自磷酸化作用外[55–56],其他的一些因子也参与介导PHYA的磷酸化和去磷酸化修饰。如燕麦的丝氨酸/苏氨酸特异性蛋白磷酸酶FyPP可以去磷酸化燕麦的PHYA[63]。同时,燕麦FyPP/PAPP5蛋白磷酸酶与PHYA蛋白直接互作,并特异性的去磷酸化Pfr形式的PHYA,其作用位点为铰链区的Ser-598的磷酸根[57–58](图 3)。

最近研究表明,拟南芥PHYA蛋白铰链区的3个氨基酸位点Ser-590、Thr-593、Ser-602均可以被磷酸化,这些位点的磷酸化调节了PHYA的生物活性[4, 11](图 3)。同时,拟南芥PHYA的磷酸化形式是由细胞核中的Pfr形式产生的,且磷酸化的PHYA可能是活性最强的形式[4]。

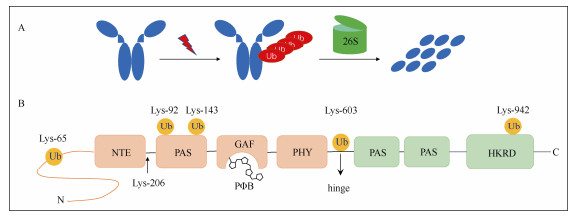

3.2 泛素化修饰在真核生物中,蛋白质的降解主要依赖于一类称为泛素的小分子降解途径。泛素分子在泛素激活酶、结合酶和连接酶等的作用下,对靶蛋白进行特异性修饰的过程。PHYA是最早被发现发生泛素化修饰的光受体蛋白[59–61]。

近年来,高通量蛋白质组学分析表明,拟南芥PHYA蛋白上存在6个泛素化修饰的赖氨酸位点, 这些修饰位点位于不同的结构域上,黄化的拟南芥幼苗照射红光后,这些位点泛素化水平迅速增加,引起PHYA被26S蛋白酶体途径快速降解。然而,在添加26S蛋白酶体抑制剂MG132处理后,仅能微弱的减缓PHYA蛋白的降解,表明除了26S蛋白酶体途径,其它未知的途径也参与到PHYA的泛素化降解途径[12](图 4)。此外,另一项研究表明,拟南芥PHYA蛋白第206位赖氨酸位点主要介导了PHYA蛋白的泛素化降解,幼苗照射红光后,该位点突变为精氨酸后PHYA的泛素化水平明显下降[13]。

|

图 4 拟南芥PHYA发生泛素化修饰和降解。A: 照光后发生泛素化并被26S蛋白酶体途径降解; B: 6个赖氨酸位点发生泛素化修饰。 Fig. 4 Arabidopsis PHYA is ubiquitinated and degraded. A: Ubiquitinated after light and degraded by 26S-proteasome pathway; B: Six lysine sites are ubiquitinated. |

除已报道的磷酸化和泛素化修饰,PHYA也可能存在着其他翻译后修饰作用。高通量蛋白质乙酰化组学分析表明,在早期发育的水稻(Oryza sativa)种子中,PHYA的285位赖氨酸位点发生乙酰化修饰[64],表明乙酰化修饰可能参与调控水稻PHYA的生物学功能。由于赖氨酸残基不仅可以发生泛素化和乙酰化修饰,还可以发生小泛素化修饰。在拟南芥PHYA上鉴定发生泛素化修饰的赖氨酸位点,也可能是小泛素化和乙酰化等修饰方式发生的潜在位点。这些修饰如何协同调控PHYA蛋白稳定性及生物学功能,仍有待进一步的研究。

4 讨论和展望前人研究表明,有生理活性的Pfr形式的PHYA通过多种途径调控光响应基因的表达:(1) PHYA在照光入核后与PIFs转录因子互作,引起PIFs的泛素化降解从而调节下游基因的表达[30–36];(2) PHYA入核后抑制COP1和SPA形成有功能的E3泛素连接酶复合体,促进转录因子如HY5、FHY3和HFR1的累积,进而启动光响应基因表达[42–48];(3) PHYA入核后直接结合光响应基因启动子并调控其表达[9]。以上研究充分揭示了PHYA间接调控基因转录的作用机制,然而,PHYA如何直接参与调控光响应基因的表达,其机制仍未探明。表观遗传修饰如组蛋白乙酰化和甲基化修饰在调节染色质结构和基因表达过程中起到重要的作用[65–66]。在后续的研究中,鉴定PHYA互作的表观遗传因子,解析PHYA对染色质结构的影响,将有助于阐明PHYA直接调控光响应基因表达的分子机制。

近期的研究表明,PHYA活性和稳定性受到磷酸化和泛素化等多种翻译后修饰调节。拟南芥PHYA铰链区3个位点Ser-590、Thr-593和Ser-602的磷酸化修饰调节了PHYA的生物活性[4, 11]。拟南芥PHYA蛋白上6个赖氨酸发生泛素化,这些修饰降低了PHYA的稳定性[12–13]。然而,植物体内哪些激酶参与调节这些位点的磷酸化?PHYA的泛素化修饰被哪些因子动态调节?此外,水稻中发现的PHYA的乙酰化修饰有何生物学作用?在后续研究中,进一步鉴定介导PHYA翻译后修饰的上游因子,将有助于更深入的揭示PHYA活性调节以及参与远红光信号转导的分子机制。

尽管PHYA的生物学功能尚未完全阐明,但其已知生化功能特性也为农作物的改良育种提供了重要的思路。最近,利用植物PHYA能够灵敏感光,以及与伴侣蛋白FHY1在不同波长光下结合(660 nm)或分离(730 nm)的特点,研究人员开发出了一种光依赖的转录激活系统,该系统具有超高的光灵敏度并能高倍的诱导基因表达,该系统有望在农作物性状的改良中得到应用[67]。同时,光敏色素不仅是感受光信号的蛋白,也是感知环境温度的受体因子[68], 针对全球变暖的环境问题,我们可以利用光敏色素感受光和温度的特性,可以对植物光敏色素进行改造,获得更加耐受高温的农作物。此外,PHYA具备独特的在黑暗中积累而在光下降解的特性,这一特性可以作为一种分子开关,精确地调节农作物重要代谢物的生物合成。

| [1] |

JIAO Y L, LAU O S, DENG X W. Light-regulated transcriptional net-works in higher plants[J]. Nat Rev Genet, 2007, 8(3): 217-230. DOI:10.1038/nrg2049 |

| [2] |

GALVÃ O V C, FANKHAUSER C. Sensing the light environment in plants: Photoreceptors and early signaling steps[J]. Curr Opin Neuro-biol, 2015, 34: 46-53. DOI:10.1016/j.conb.2015.01.013 |

| [3] |

WANG Q, LIN C T. Mechanisms of cryptochrome-mediated photo-responses in plants[J]. Annu Rev Plant Biol, 2020, 71: 103-129. DOI:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-100300 |

| [4] |

ZHOU Y Y, YANG L, DUAN J, et al. Hinge region of Arabidopsis PHYA plays an important role in regulating phyA function[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2018, 115(50): E11864-E11873. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1813162115 |

| [5] |

KIRCHER S, KOZMA-BOGNAR L, KIM L, et al. Light quality-dependent nuclear import of the plant photoreceptors phytochrome A and B[J]. Plant Cell, 1999, 11(8): 1445-1456. DOI:10.1105/tpc.11.8.1445 |

| [6] |

KIM L, KIRCHER S, TOTH R, et al. Light-induced nuclear import of phytochrome-A: GFP fusion proteins is differentially regulated in transgenic tobacco and Arabidopsis[J]. Plant J, 2000, 22(2): 125-133. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00729.x |

| [7] |

SHEERIN D J, MENON C, ZUR OVEN-KROCKHAUS S, et al. Light-activated phytochrome A and B interact with members of the SPA family to promote photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis by reor-ganizing the COP1/SPA complex[J]. Plant Cell, 2015, 27(1): 189-201. DOI:10.1105/tpc.114.134775 |

| [8] |

AL-SADY B, NI W M, KIRCHER S, et al. Photoactivated phyto-chrome induces rapid PIF3 phosphorylation prior to proteasome-mediated degradation[J]. Mol Cell, 2006, 23(3): 439-446. DOI:10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.011 |

| [9] |

CHEN F, LI B S, LI G, et al. Arabidopsis phytochrome A directly targets numerous promoters for individualized modulation of genes in a wide range of pathways[J]. Plant Cell, 2014, 26(5): 1949-1966. DOI:10.1105/TPC.114.123950 |

| [10] |

JENSEN O N. Interpreting the protein language using proteomics[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2006, 7(6): 391-403. DOI:10.1038/nrm1939 |

| [11] |

ZHANG S M, LI C, ZHOU Y Y, et al. TANDEM ZINC-FINGER/PLUS3 is a key component of phytochrome a signaling[J]. Plant Cell, 2018, 30(4): 835-852. DOI:10.1105/tpc.17.00677 |

| [12] |

AGUILAR-HERNÁNDEZ V, KIM D Y, STANKEY R J, et al. Mass spectrometric analyses reveal a central role for ubiquitylation in remo-deling the Arabidopsis proteome during photomorphogenesis[J]. Mol Plant, 2017, 10(6): 846-865. DOI:10.1016/j.molp.2017.04.008 |

| [13] |

RATTANAPISIT K, CHO M H, BHOO S H. Lysine 206 in Arabi-dopsis phytochrome A is the major site for ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation[J]. J Biochem, 2016, 159(2): 161-169. DOI:10.1093/jb/mvv085 |

| [14] |

WANG Q, ZUO Z C, WANG X, et al. Photoactivation and inactivation of Arabidopsis cryptochrome 2[J]. Science, 2016, 354(6310): 343-347. DOI:10.1126/science.aaf9030 |

| [15] |

LIN C T, YANG H Y, GUO H W, et al. Enhancement of blue-light sensitivity of Arabidopsis seedlings by a blue light receptor crypto-chrome 2[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1998, 95(5): 2686-2690. DOI:10.1073/pnas.95.5.2686 |

| [16] |

SULLIVAN S, WAKSMAN T, PALIOGIANNI D, et al. Regulation of plant phototropic growth by NPH3/RPT2-like substrate phosphorylation and 14-3-3 binding[J]. Nat Commun, 2021, 12: 6129. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-26333-5 |

| [17] |

LI J G, LI G, WANG H Y, et al. Phytochrome signaling mechanisms[J]. Arabidopsis Book, 2011, 9: e0148. DOI:10.1199/tab.0148 |

| [18] |

QUAIL P H. An emerging molecular map of the phytochromes[J]. Plant Cell Environ, 1997, 20(6): 657-665. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-3040.1997.d01-108.x |

| [19] |

FANKHAUSER C. The phytochromes, a family of red/far-red absorbing photoreceptors[J]. J Biol Chem, 2001, 276(15): 11453-11456. DOI:10.1074/jbc.R100006200 |

| [20] |

NAGATANI A. Light-regulated nuclear localization of phytochromes[J]. Curr Opin Plant Biol, 2004, 7(6): 708-711. DOI:10.1016/j.pbi.2004.09.010 |

| [21] |

ROCKWELL N C, SU Y S, LAGARIAS J C. Phytochrome structure and signaling mechanisms[J]. Annu Rev Plant Biol, 2006, 57: 837-858. DOI:10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144208 |

| [22] |

QUAIL P H. Phytochrome photosensory signalling networks[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2002, 3(2): 85-93. DOI:10.1038/nrm728 |

| [23] |

TERRY M J, MCDOWELL M T, LAGARIAS J C. (3Z)-and (3E)-phytochromobilin are intermediates in the biosynthesis of the phyto-chrome chromophore[J]. J Biol Chem, 1995, 270(19): 11111-11118. DOI:10.1074/jbc.270.19.11111 |

| [24] |

REED J W, NAGATANI A, ELICH T D, et al. Phytochrome A and phytochrome B have overlapping but distinct functions in Arabidopsis development[J]. Plant Physiol, 1994, 104(4): 1139-1149. DOI:10.1104/pp.104.4.1139 |

| [25] |

DEHESH K, FRANCI C, PARKS B M, et al. Arabidopsis HY8 locus encodes phytochrome A[J]. Plant Cell, 1993, 5(9): 1081-1088. DOI:10.1105/tpc.5.9.1081 |

| [26] |

NAGATANI A, REED J W, CHORY J. Isolation and initial characteri-zation of Arabidopsis mutants that are deficient in phytochrome A[J]. Plant Physiol, 1993, 102(1): 269-277. DOI:10.1104/pp.102.1.269 |

| [27] |

WHITELAM G C, JOHNSON E, PENG J, et al. Phytochrome A null mutants of Arabidopsis display a wild-type phenotype in white light[J]. Plant Cell, 1993, 5(7): 757-768. DOI:10.1105/tpc.5.7.757 |

| [28] |

NEFF M M, CHORY J. Genetic interactions between phytochrome A, phytochrome B, and cryptochrome 1 during Arabidopsis development[J]. Plant Physiol, 1998, 118(1): 27-35. DOI:10.1104/pp.118.1.27 |

| [29] |

GENOUD T, SCHWEIZER F, TSCHEUSCHLER A, et al. FHY1 mediates nuclear import of the light-activated phytochrome A photo-receptor[J]. PLoS Genet, 2008, 4(8): e1000143. DOI:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000143 |

| [30] |

BU Q Y, CASTILLON A, CHEN F L, et al. Dimerization and blue light regulation of PIF1 interacting bHLH proteins in Arabidopsis[J]. Plant Mol Biol, 2011, 77(4): 501-511. DOI:10.1007/s11103-011-9827-4 |

| [31] |

SHIN J, KIM K, KANG H, et al. Phytochromes promote seedling light responses by inhibiting four negatively-acting phytochrome-interacting factors[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2009, 106(18): 7660-7665. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0812219106 |

| [32] |

LEIVAR P, MONTE E, OKA Y, et al. Multiple phytochrome-inter-acting bHLH transcription factors repress premature seedling photo-morphogenesis in darkness[J]. Curr Biol, 2008, 18(23): 1815-1823. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.058 |

| [33] |

CHOI H, JEONG S, KIM D S, et al. The homeodomain-leucine zipper ATHB23, a phytochrome B-interacting protein, is important for phyto-chrome B-mediated red light signaling[J]. Physiol Plantarum, 2014, 150(2): 308-320. |

| [34] |

LEIVAR P, MONTE E, AL-SADY B, et al. The Arabidopsis phytochrome-interacting factor PIF7, together with PIF3 and PIF4, regulates responses to prolonged red light by modulating phyB levels[J]. Plant Cell, 2008, 20(2): 337-352. DOI:10.1105/tpc.107.052142 |

| [35] |

KHANNA R, HUQ E, KIKIS E A, et al. A novel molecular recognition motif necessary for targeting photoactivated phytochrome signaling to specific basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors[J]. Plant Cell, 2004, 16(11): 3033-3044. DOI:10.1105/tpc.104.025643 |

| [36] |

LEE N, CHOI G. Phytochrome-interacting factor from Arabidopsis to liverwort[J]. Curr Opin Plant Biol, 2017, 35: 54-60. DOI:10.1016/j.pbi.2016.11.004 |

| [37] |

HOECKER U. The activities of the E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1/SPA, a key repressor in light signaling[J]. Curr Opini Plant Biol, 2017, 37: 63-69. DOI:10.1016/j.pbi.2017.03.015 |

| [38] |

LAU O S, DENG X W. The photomorphogenic repressors COP1 and DET1: 20 years later[J]. Trends Plant Sci, 2012, 17: 584-593. DOI:10.1016/j.tplants.2012.05.004 |

| [39] |

SAIJO Y, SULLIVAN J A, WANG H Y, et al. The COP1-SPA1 interaction defines a critical step in phytochrome A-mediated regulation of HY5 activity[J]. Genes Dev, 2003, 17(21): 2642-2647. DOI:10.1101/gad.1122903 |

| [40] |

SEO H S, YANG J Y, ISHIKAWA M, et al. LAF1 ubiquitination by COP1 controls photomorphogenesis and is stimulated by SPA1[J]. Nature, 2003, 423(6943): 995-999. DOI:10.1038/nature01696 |

| [41] |

HAN X, HUANG X, DENG X W. The photomorphogenic central repressor COP1: Conservation and functional diversification during evolution[J]. Plant Commun, 2020, 1(3): 100044. DOI:10.1016/j.xplc.2020.100044 |

| [42] |

XU D Q, JIANG Y, LI J G, et al. BBX21, an Arabidopsis B-box protein, directly activates HY5 and is targeted by COP1 for 26S proteasome-mediated degradation[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2016, 113(27): 7655-7660. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1607687113 |

| [43] |

SRIVASTAVA A K, SENAPATI D, SRIVASTAVA A, et al. Short hypocotyl in white light1 interacts with elongated hypocotyl5(HY5) and constitutive photomorphogenic1(COP1) and promotes COP1-mediated degradation of HY5 during Arabidopsis seedling development[J]. Plant Physiol, 2015, 169(4): 2922-2934. DOI:10.1104/pp.15.01184 |

| [44] |

LUO Q, LIAN H L, HE S B, et al. COP1 and phyB physically interact with PIL1 to regulate its stability and photomorphogenic development in Arabidopsis[J]. Plant Cell, 2014, 26(6): 2441-2456. DOI:10.1105/tpc.113.121657 |

| [45] |

GANGAPPA S N, CROCCO C D, JOHANSSON H, et al. The Arabi-dopsis B-BOX protein BBX25 interacts with HY5, negatively regu-lating BBX22 expression to suppress seedling photomorphogenesis[J]. Plant Cell, 2013, 25(4): 1243-1257. DOI:10.1105/tpc.113.109751 |

| [46] |

CHEN D Q, XU G, TANG W J, et al. Antagonistic basic Helix-Loop-Helix/bZIP transcription factors form transcriptional modules that integrate light and reactive oxygen species signaling in Arabidopsis[J]. Plant Cell, 2013, 25(5): 1657-1673. DOI:10.1105/tpc.112.104869 |

| [47] |

ANG L H, CHATTOPADHYAY S, WEI N, et al. Molecular interaction between COP1 and HY5 defines a regulatory switch for light control of Arabidopsis development[J]. Mol Cell, 1998, 1(2): 213-222. DOI:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80022-2 |

| [48] |

SAIJO Y, ZHU D M, LI J G, et al. Arabidopsis COP1/SPA1 complex and FHY1/FHY3 associate with distinct phosphorylated forms of phytochrome A in balancing light signaling[J]. Mol Cell, 2008, 31(4): 607-613. DOI:10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.003 |

| [49] |

LI Z L, SHEERIN D J, VON ROEPENACK-LAHAYE E, et al. The phytochrome interacting proteins ERF55 and ERF58 repress light-induced seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Nat Commun, 2022, 13: 1656. DOI:10.1038/s41467-022-29315-3 |

| [50] |

LAPKO V N, JIANG X Y, SMITH D L, et al. Mass spectrometric characterization of oat phytochrome A: Isoforms and posttranslational modifications[J]. Protein Sci, 1999, 8(5): 1032-1044. DOI:10.1110/ps.8.5.1032 |

| [51] |

KIM J I, SHEN Y, HAN Y J, et al. Phytochrome phosphorylation modulates light signaling by influencing the protein-protein interaction[J]. Plant Cell, 2004, 16(10): 2629-2640. DOI:10.1105/tpc.104.023879 |

| [52] |

JORDAN E T, MARITA J M, CLOUGH R C, et al. Characterization of regions within the N-terminal 6-kilodalton domain of phytochrome A that modulate its biological activity[J]. Plant Physiol, 1997, 115(2): 693-704. DOI:10.1104/pp.115.2.693 |

| [53] |

KNEISSL J, SHINOMURA T, FURUYA M, et al. A rice phytochrome A in Arabidopsis: The role of the N-terminus under red and far-red light[J]. Mol Plant, 2008, 1(1): 84-102. DOI:10.1093/mp/ssm010 |

| [54] |

STOCKHAUS J, NAGATANI A, HALFTER U, et al. Serine-to-alanine substitutions at the amino-terminal region of phytochrome A result in an increase in biological activity[J]. Genes Dev, 1992, 6: 2364-2372. DOI:10.1101/gad.6.12a.2364 |

| [55] |

HAN Y J, KIM H S, KIM Y M, et al. Functional characterization of phytochrome autophosphorylation in plant light signaling[J]. Plant Cell Physiol, 2010, 51(4): 596-609. DOI:10.1093/pcp/pcq025 |

| [56] |

HAN Y J, KIM H S, SONG P S, et al. Autophosphorylation desensi-tizes phytochrome signal transduction[J]. Plant Sign Behav, 2010, 5(7): 868-871. DOI:10.4161/psb.5.7.11898 |

| [57] |

RYU J S, KIM J I, KUNKEL T, et al. Phytochrome-specific type 5 phosphatase controls light signal flux by enhancing phytochrome stability and affinity for a signal transducer[J]. Cell, 2005, 120(3): 395-406. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.019 |

| [58] |

RUBIO V, DENG X W. Phy tunes: Phosphorylation status and phyto-chrome-mediated signaling[J]. Cell, 2005, 120(3): 290-292. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.023 |

| [59] |

SHANKLIN J, JABBEN M, VIERSTRA R D. Red light-induced formation of ubiquitin-phytochrome conjugates: Identification of possible intermediates of phytochrome degradation[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1987, 84(2): 359-363. DOI:10.1073/pnas.84.2.359 |

| [60] |

JABBEN M, SHANKLIN J, VIERSTRA R D. Red light-induced accumulation of ubiquitin-phytochrome conjugates in both monocots and dicots[J]. Plant Physiol, 1989, 90(2): 380-384. DOI:10.1104/PP.90.2.380 |

| [61] |

JABBEN M, SHANKLIN J, VIERSTRA R D. Ubiquitin-phytochrome conjugates: Pool dynamics during in vivo phytochrome degradation[J]. J Biol Chem, 1989, 264(9): 4998-5005. |

| [62] |

COHEN P. The origins of protein phosphorylation[J]. Nat Cell Biol, 2002, 4(5): E127-E130. DOI:10.1038/ncb0502-e127 |

| [63] |

KIM D H, KANG J G, YANG S S, et al. A phytochrome-associated protein phosphatase 2A modulates light signals in flowering time control in Arabidopsis[J]. Plant Cell, 2002, 14(12): 3043-3056. DOI:10.1105/tpc.005306 |

| [64] |

WANG Y F, HOU Y X, QIU J H, et al. A quantitative acetylomic analysis of early seed development in rice (Oryza sativa L.)[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2017, 18(7): 1376. DOI:10.3390/ijms18071376 |

| [65] |

LIU X C, CHEN C Y, WANG K C, et al. PHYTOCHROME INTER-ACTING FACTOR3 associates with the histone deacetylase HDA15 in repression of chlorophyll biosynthesis and photosynthesis in etiolated Arabidopsis seedlings[J]. Plant Cell, 2013, 25(4): 1258-1273. DOI:10.1105/tpc.113.109710 |

| [66] |

ZHAO L M, PENG T, CHEN C Y, et al. HY5 interacts with the histone deacetylase HDA15 to repress hypocotyl cell elongation in photomor-phogenesis[J]. Plant Physiol, 2019, 180(3): 1450-1466. DOI:10.1104/pp.19.00055 |

| [67] |

ZHOU Y, KONG D Q, WANG X Y, et al. A small and highly sensitive red/far-red optogenetic switch for applications in mammals[J]. Nat Biotechnol, 2022, 40(2): 262-272. DOI:10.1038/s41587-021-01036-w |

| [68] |

LEGRIS M, KLOSE C, BURGIE E S, et al. Phytochrome B integrates light and temperature signals in Arabidopsis[J]. Science, 2016, 354(6314): 897-900. DOI:10.1126/science.aaf5656 |

2024, Vol. 32

2024, Vol. 32