Phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) is an important, soluble, rate-limited kinase used for basic metabolism in all organisms[1]. In plants, PGK participates in the Calvin cycle and glycolysis by catalyzing the release and transfer of high-energy phosphate groups between 3-phosphoglycerate (PGA) and 1, 3-diphosphoglycerate (DPGA) and then catalyzing the reversible conversion of PGA and DPGA[2]. Glucose phosphate isomerase (GPI) is a multifunctional dimer protein in organisms that plays an important role in the carbohydrate meta- bolism cycle[3]. It catalyzes and breaks the molecular ring structure of fructose-6-phosphate (F6P) or glucose- 6-phosphate (G6P) and transfers the intramolecular proton via its enzymatic acid-base catalytic mechanism and finally the two hexoses undergo reversible isome- rization[2, 4].

PGK exists in only one form in prokaryotes, while in most eukaryotes, there are 2-3 isozymes with different subcellular localizations[1, 5]. PGK in plants is divided into two localization subtypes: cytosolic and chloroplast/plastidial PGK. Cytosol PGK mainly parti- cipates in cytoplasmic matrix glycolysis, while chloro- plastic/plastidial PGK is mainly involved in the dual metabolic pathway of the Calvin cycle and chloro- plastic/plastidial glycolysis[6]. GPI exists as a single form of cytosolic GPI in most animals and microorga- nisms, while there is also a plastidial GPI in plant cells[7]. Cytosolic GPI mainly participates in sucrose synthesis and glycolysis, and plastidial GPI is mainly involved in the metabolism of the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (OPPP) and starch synthesis[8–9].

At present, research on PGK and GPI mainly focuses on clinical diagnosis[10-12]. There are relatively few studies on the protein subcellular localization, biological function and gene expression analysis of isoenzymes encoding different subtypes of PGK and GPI in plants, and the researches of the two enzymes in plants are mainly concentrated on annual plants, such as Arabidopsis thaliana or Helianthus annuus[13-16]. In this research, we cloned the PGK1 and GPIC genes of masson pine, which encode phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1) and cytosolic glucose phosphate isomerase (CPIC), respectively. To explore the function of PmPGK1 and PmGPIC, bioinformatic analysis, sub- cellular localization analysis and quantitative real- time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis based on tissue-specific expression, low temperature and high CO2 stress were performed. The results of this research could advance our understanding of PGK and GPI in Masson pine and other plants.

1 Materials and methods 1.1 Test materialsThe plant material used for rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) analysis was derived from germi- nated seeds of masson pine (Pinus massoniana). The protoplast material used for subcellular localization was obtained from wild-type Arabidopsis thaliana (Columbia ecotype) at 3-4-week-old and not flowered. A laboratory-preserved pJIT166 transient expression vector was used for subcellular localization. Materials for tissue-specific expression were collected from 15- year-old masson pine in the arboreal garden of Nan- jing Forestry University. The annual masson pine seedlings were used for expression analysis under low-temperature and elevated-CO2 stress, which were provided by Fujian Baisha Forest Farm and then planted in soil (nutrient soil∶vermiculite∶perlite= 1∶1∶1) in laboratory in September, 2018. The seedlings were grown in a naturally chamber with a cycle of 10 h light/14 h dark, day/night temperature of 30℃/26℃, and a relative humidity of 60%, with a slow seedling stage for about 15 days. Then the seedlings with the same growth state were selected for the following experiment.

1.2 Total RNA extraction and full-length gene cloneTotal RNA was extracted from masson pine seedlings followed the RNAprep Pure RNA extraction kit (Tiangen, Beijing). The concentration and quality of the RNA were detected by a NanoDrop fluorometer (ThermoFisher, MA, USA) and electrophoresis, respec- tively. First-strand cDNA was synthesized by using TransScript® One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen, Beijing).

The PmPGK1 and PmGPIC sequences were screened out after homology comparison between the PGK1 and GPIC gene sequences of Arabidopsis tha- liana obtained from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and the masson pine transcriptome database (NCBI access No.: PRJNA561037). The cloning and amplification of intermediate fragments were carried out using the amplification primers (Table 1). Then, according to the intermediate sequence, the 5ʹ/3ʹ RACE- specific primer was used to amplify the 5ʹ/3ʹ end sequence according to the instructions of the SMA- RTer RACE 5ʹ/3ʹ Kit (TaKaRa, Beijing). The full- length of PmPGK1 and PmGPIC cDNA was obtained after sequence alignment and splicing predicttion, and conserved domains from the NCBI database were used for PmPGK1 and PmGPIC conserved domain analysis.

| Table 1 Sequences of primers used in this study |

Blastn and Blastp from the NCBI were used to compare the homologous sequences of PmPGK1 and PmGPIC cDNA and the amino acid sequences of their encoded proteins. Then, MEGA 7.0 was used to con-struct PmPGK1 and PmGPIC phylogenetic trees by the neighbor-joining method. WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/) was used to analyze the subcellular localization of PmPGK1 and PmGPIC proteins.

1.4 Subcellular localizationpJIT166 plasmid was double digested (restriction enzyme cutting sites: Hind Ⅲ and Xba Ⅰ). The recom- binant expression vector was constructed according to the ClonExpress Ⅱ One-Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing). The recombinant plasmid was extracted according to the instructions of the Plasmid Maxi Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) after transformation into Escherichia coli and culture expansion. According to the manufacturer's instructions (Real-time Biotech, Beijing), approximately 10 large and plump wild-type Arabidopsis thaliana (Columbia ecotype) leaves were selected and cut into thin strips with a width of 0.5-1.0 mm to prepare protoplasts, and then, the pJIT166 recom- binant plasmid (> 1 μg/μL) was transformed into the prepared protoplast (10 μL). Finally, the above solu- tion was put it in a 22℃-25℃ dark environment for 14-16 h of incubation, and the fluorescence reaction was recorded at 488 and 543 nm by fluorescence microscopy. Protoplasts with empty vector accom- panied by green fluorescent protein (GFP) were used as the control group (CK group).

1.5 Expression patternsFor tissue-specific expression analysis, total RNA from 5 tissues, including new leaves (NL), old leaves (OL), new stems (NS), flowers (F) and roots (R), was extracted with three biological replicates for each treatment using a Plant RNA Isolation Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing). Then, first-strand cDNA was syn- thesized with FastKing gDNA Dispelling RT Super- Mix (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For cold stress, annual seedlings were placed in a refrigerator at 4℃ and the seedling leaves were collected at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 h, respectively. For elevated-CO2 stress, the seedlings were moved into a growth chamber with 10 h light/14 h dark at 25℃. Air containing approximately 400- 450 mg/m3 CO2 (approximately two times the ambient CO2 concentration) was injected into the growth chamber constantly for at least 24 h. Then, the seedling leaves were sampled after 0, 6, 12 and 24 h of treatment. For qRT-PCR, the mixtures consisted of 10 µL of 2×ChamQTM Universal SYBR® qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing), 0.4 µL of forward primer and reverse primer, 2 µL of cDNA, and 7.2 µL of ddH2O. The qRT-PCR program consisted of three stages: 95℃ for 30 s (preincubation), 95℃ for 10 s, 60℃ for 30 s, and 72℃ for 30 s, cycling 40 times (amplification), and 95℃ for 15 s, 60℃ for 1 min and 95℃ for 15 s (melting curves). QRT-PCR quality was estimated based on the melting curves. PmActin2 (NCBI Accession No.: KM496525.1) was used as the internal control[17]. The gene-specific primers employed are shown in Table 1. Three independent technical replicates were performed for each treatment. Quan- tification was achieved using comparative cycle threshold (Ct) values, and gene expression levels were calculated using the 2–∆∆CT method[17].

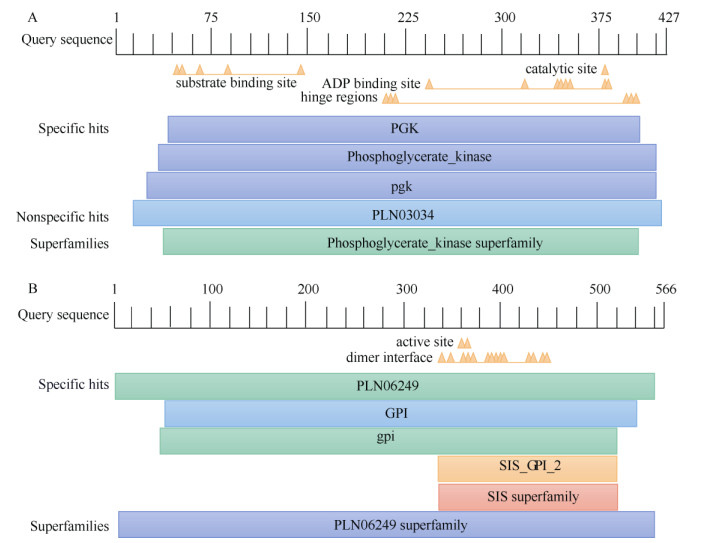

2 Results 2.1 Full-length clone of PmPGK1 and PmGPICThe intermediate fragments of PmPGK1 and PmGPIC were 1 564 and 1 305 bp, respectively. The 5ʹ/3ʹ RACE sequences of PmPGK1 were 297 and 1 225 bp, respectively, and those of PmGPIC were 1 056 and 1 117 bp, respectively. After sequence alignment and splicing, it was found that the full-length of PmPGK1 and PmGPIC were 1 848 bp (NCBI Acce- ssion No.: MT586614) and 2 106 bp (NCBI Accession No.: MT591683), respectively (Table 2). According to ORF Finder analysis, the 5ʹ/3ʹ cDNA ends of Pm- PGK1 had 93 and 324 bp untranslated regions (UTRs), respectively. The open reading frame (ORF) of Pm- PGK1 covered 1 524 bp, encoding 507 amino acids. In contrast, the 5ʹ/3ʹ cDNA ends of PmGPIC had 146 and 259 bp UTRs, respecttively. The ORF of PmGPIC covered 1 701 bp, encoding 566 amino acids. Conserved domain analysis showed that PmPGK1 and PmGPIC were members of the phosphoglycerate kinase super- family and PLN06249 superfamily, respectively (Fig. 1).

| Table 2 Sequence of full-length cDNA of PmPGK1 and PmGPIC |

|

Fig. 1 Conserved domain of amino acids of PmPGK1 (A) and PmGPIC (B) |

The Blastn comparison results showed that the similarity of PGK1 between P. massoniana and P. pinaster (the only species reported PGK1 sequence from gymnosperms) was 98.53%, and that between P. massoniana and angiosperms was 73%-80%. The similarity of PmGPIC with GPIC in Cedrus libani reached 93.66%, and with those in Ginkgo biloba, Encephalartos barteri, and Cryptomeria japonica was 85.60%, 84.23% and 83.64%, respectively.

The similarity of PGK1 between P. massoniana and P. pinaster was 99.01%. In terms of known angiosperm plants, the similarity with the chloro- plastic PGK of Carica papaya, Asparagus officinalis and Prosopis alba was 87.65%, 85.22% and 84.28%, respectively, and that with the cytosolic PGK of Cajanus cajan, Glycine max and Dendrobium catenatum were 87.92%, 87.89% and 83.56%, respecttively. For GPIC, among the known angiosperms, the simila- rities between Masson pine and Ananas comosus, Elaeis guineensis and Apostasia shenzhenica were higher than those with others, reaching 81.16%, 80.86% and 80.43%, respectively.

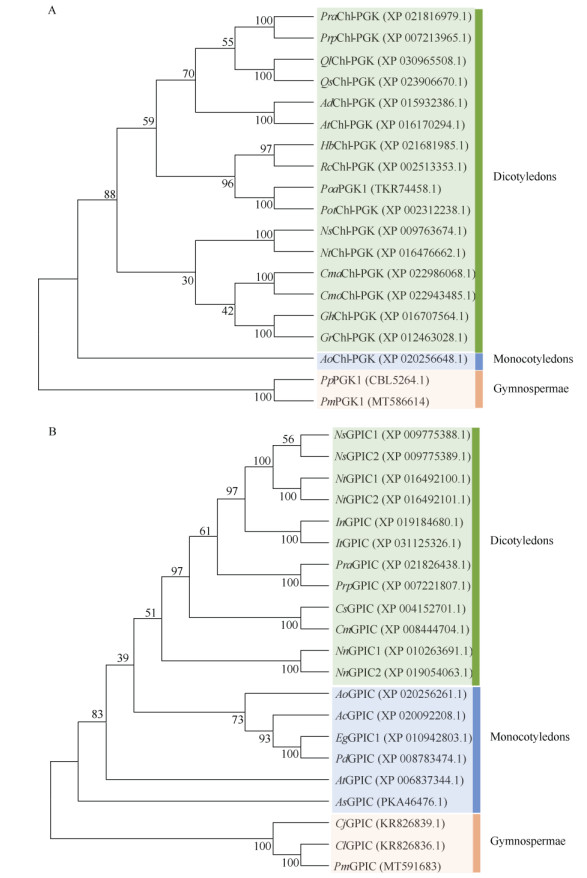

According to PGK phylogenetic analysis, P. massoniana clustered with P. pinaster firstly, showing the closest relationship, and then clustered with angio- sperms (Fig. 2: A). For GPIC, masson pine, Cedrus libani, Cryptomeria japonica and Ginkgo biloba were clustered initially, with a confidence of 100%, and then sequentially clustered with monocotyledonous or dicotyledonous plants (Fig. 2: B). These results were consistent with the homology comparison results.

|

Fig. 2 Phylogenetic tree of PGK1 (A) and GPIC (B). Pra: Prunus avium; Prp: P. persica; Ql: Quercus lobata; Qs: Q. suber; Ad: Arachis duranensis; Ai: A. ipaensis; Hb: Hevea brasiliensis; Rc: Ricinus communis; Poa: Populus alba; Pot: P. trichocarpa; Ns: Nicotiana sylvestris; Nt: N. tabacum; Cma: Cucurbita maxima; Cmo: C. moschata; Cs: C. sativus; Cm: C. melo; Gh: Gossypium hirsutum; Gr: G. raimondii; Ao: Asparagus officinalis; Pp: Pinus pinaster; Pm: P. massoniana; In: Ipomoea nil; It: I. triloba; Nn: Nelumbo nucifera; Ac: Ananas comosus; Eg: Elaeis guineensis; Pd: Phoenix dactylifera; At: Amborella trichopoda; As: Apostasia shenzhenica; Cj: Cryptomeria japonica; Cl: Cedrus libani. |

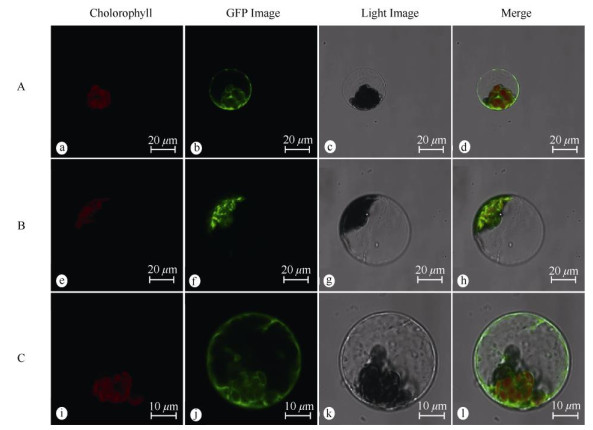

The localization results showed that the empty vector GFP fluorescence signal was expressed in the cell membrane, cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 3: a-d). WoLF PSORT predicted that PmPGK1 was located in the cytosol, which was different from the subcellular localization result that it was located in the chloroplast (Fig. 3: e-h). The fluorescence signal of PmGPIC filled the cytoplasmic matrix (Fig. 3: i-l), which was consistent with the prediction of WoLF PSORT.

|

Fig. 3 Subcellular localization of PmPGK1 and PmGPIC proteins in protoplast of Arabidopsis thaliana. A: pJIT166-GFP; B: pJIT166-PmPGK1-GFP; C: pJIT166-PmGPIC-GFP; a, e, f: Chloroplast autofluorescence field; b, f, j: GFP field; c, g, k: Bright field; d, h, l: Merged pictures. |

Tissue-specific expression analysis revealed that the expression of PmPGK1 in new leaf (NL) was the highest, followed by new stem (NS) and old leaf (OL). The expression difference among three tissues was relatively small. The lowest expression was observed in flower (F), which had significant difference from that in other tissues (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4: A). For Pm- GPIC, the expression was the highest in old leaf and nearly zero in the roots (R). There were significant differences among all tissues except new leaf and flower (Fig. 4: A).

|

Fig. 4 Expression of PmPGK1 and PmGPIC in different tissues (A), under low-temperature stress (B) and high-CO2 stress (C). NL: New leaf; OL: Old leaf; NS: New stem; F: Flower; R: Root. Different letters upon column indicate significant differences at 0.05 level by Duncan test. |

Under low-temperature stress within 12 h, the expression of PmPGK1 and PmGPIC decreased with the time, and the decrease in PmGPIC was more obvious than that in PmPGK1. The expression level of PmPGK1 decreased to the lowest level after 12 h stress, showing a significant difference from that in other groups (Fig. 4: B). On the other hand, along the time, there was no significant difference in expression of PmGPIC among the experimental groups (Fig. 4: B). Under elevated-CO2 stress, PmPGK1 showed signi- ficant differences among different time and showing a trend of decreasing-increasing-decreasing (Fig. 4: C). The expression of PmGPIC did not change signify- cantly under high-CO2 stress and within 24 h (Fig. 4: C).

3 Conclusion and discussionBoth of PGK and GPI have two localization sub- types in plant cells, i.e. cytoplasmic and plastidial. Isoenzymes of different localization types perform different functions in cell metabolism[1, 7]. According to the subcellular localization, it was found that PmPGK1 was located in the chloroplast, belonging to chloroplastic/plastidial subtype, mainly involved in Calvin cycle and chloroplast/plastid glycolytic meta- bolism and catalyzes the reversible reaction between PGA and DPGA[6, 13–14]. This result is the same as AtPGK1 in Arabidopsis thaliana by Rosa-Téllez et al.[13], but contrary to that of Huang et al.[18], who proved that PGK1 was localized in the cytosol. PmGPIC was located in the cytosol, which proved that it was mainly involved in sucrose synthesis and glycolytic metabolism in the cell matrix and catalyzed the reversible isomerization between F6P and G6P. Currently, there are no reports on the subcellular localization of plant GPI isoenzymes.

The expression of PmPGK1 in leaf was higher than that in other tissues, which was consistent with the results in Arabidopsis thaliana[13] and Brassica napus[19]. On the other hand, PmPGK1 was also expressed in root, new stem and flower, suggesting that it is involved in glycolytic metabolism in these organs. Compared with P. massoniana, PGK1 in Arabidopsis thaliana[13, 18] and Brassica napus[19] showed the highest expression in flower. This discre- pancy may be caused by some metabolic differences between perennial trees and annual herbs. PmGPIC was mainly expressed in leaves and flowers, and the expression level was highest in old leaves. Therefore, it is speculated that the transformation reaction between F6P and G6P catalyzed by PmGPIC in old leaves was stronger than that in new leaves and flowers. This result was consistent with that of Troncoso-Ponce et al.[16].

Previous studies have proven that low tempera- ture could reduce the stability of chlorophyll, the solubility of CO2 in cells and the affinity of Rubisco to CO2, directly affecting the integrity and activity of the photosynthetic system[20–21]. As important regulating enzymes in the Calvin cycle, RuBP carboxylase (Ru- BPCase), phosphoribulose kinase (PRK) and 1, 6- fructose bisphosphatase (FBP) all showed a decreasing trend of expression under low temperature stress[22–25]. The reaction product of RuBPCase and PRK was the reaction substrate of PmPGK1; therefore, the influence of low temperature on both led to a decrease in the activity of PmPGK1 and gene expression. Mean- while, the respiration metabolism of plants under low temperature stress was dominated by the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), at which time the glycolysis pathway was inhibited[26]. In addition, FBP activity was reduced under low temperature, resulting in a decrease in the catalytic substrate of PmGPIC[23, 25]. Based on the above factors, the expression of PmGPIC was more downregulated after low temperature treatment than that of PmPGK1, showing a sharp decline.

Previous studies[27] have shown that the expre- ssion of all genes in the Calvin cycle, except GAPDH, decrease under a high CO2 concentration in masson pine; therefore, it was speculated that the photo- synthetic acclimation of masson pine could be com- pleted within 6 h. In addition, it was found that an increased CO2 concentration leads to a significant increase in hexokinase (HK) activity[27], while HK strongly inhibits the activity of Rubisco and Rubisco small subunit (RbcS)[28–29], in turn decreasing the content of PGA (the direct catalytic substrate for the transformation of RuBP to PGK, resulting in a signi- ficant decrease in the expression of PGK1). According to the changes in the expression levels of the two genes, PmGPIC was less affected by CO2 stress than PmPGK1. The transcriptome sequencing results in a previous study[27] showed that the expression levels of PmGPIC were higher after treatment than those at 0 h, which was different from the finding in this experi- ment, but the overall trends of change were consistent. Invertase (INV) phosphorylates glucose and fructose to form the catalytic substrate of GPIC[2]. Under elevated CO2 conditions, the expression levels of INV and HK in Masson pine were significantly increased[27], so the expression level of PmGPIC was slightly increased after 6 h. The decrease in PmGPIC after 12 h might have been caused by gradual decreases in the accumulation of photosynthetic products and the glucose metabolic rate. In addition, since photosyn- thetic adaptation is more obvious in annual needles than in that mature needles under elevated-CO2 stress[30], more detection could be used before photosynthetic adaptation, and the response mechanism of PmPGK1 and PmGPIC could be further explored by comparison with the responses in perennial Masson pine samples.

In this study, full-length PmPGK1 and PmGPIC were cloned, and encoding proteins were belong to the plastidial and cytoplasmic subtypes, respectively. Pm- PGK1 was mainly expressed in leaves, and PmGPIC was mainly expressed in leaves and flowers. The expression of PmPGK1 and PmGPIC was inhibited under low-temperature stress, and the inhibitory effect on PmGPIC was stronger. Elevated-CO2 stress signi- fycantly inhibited the expression of PmPGK1 but had little effect on the expression of PmGPIC. The results of this study provide some references for subsequent studies on PGK and GPI in plants.

| [1] |

WU D, WU Z D, YU X B. Advance in the research of phospho-glycerate kinase[J]. China Trop Med, 2005, 5(2): 385-387. (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1009-9727.2005.02.100 |

| [2] |

WANG J Y, ZHU S G, XU C F. Biochemistry[M]. 3rd ed. Beijing: Higher Education Press, 2002: 66-79.

|

| [3] |

KUGLER W, LAKOMEK M. Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase deficiency[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol, 2000, 13(1): 89-101. DOI:10.1053/beha.1999.0059 |

| [4] |

KUNZ H H, ZAMANI-NOUR S, HÄUSLER R E, et al. Loss of cytosolic phosphoglucose isomerase affects carbohydrate metabolism in leaves and is essential for fertility of Arabidopsis[J]. Plant Physiol, 2014, 166(2): 753-765. DOI:10.1104/pp.114.241091 |

| [5] |

SHAH N, BRADBEER J W. The development of the activity of the chloroplastic and cytosolic isoenzymes of phosphoglycerate kinase during barley leaf ontogenesis[J]. Planta, 1991, 185(3): 401-406. DOI:10.1007/BF00201064 |

| [6] |

ANDERSON L E, BRYANT J A, CAROL A A. Both chloroplastic and cytosolic phosphoglycerate kinase isozymes are present in the pea leaf nucleus[J]. Protoplasma, 2004, 223(2/3/4): 103-110. DOI:10.1007/s00709-004-0041-y |

| [7] |

NOWITZKI U, FLECHNER A, KELLERMANN J, et al. Eubacterial origin of nuclear genes for chloroplast and cytosolic glucose-6-phosphate isomerase from spinach: Sampling eubacterial gene diversity in eukaryotic chromosomes through symbiosis[J]. Gene, 1998, 214(1/2): 205-213. DOI:10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00229-7 |

| [8] |

MARTIN W, HERRMANN R G. Gene transfer from organelles to the nucleus: How much, what happens, and Why?[J]. Plant Physiol, 1998, 118(1): 9-17. DOI:10.1104/pp.118.1.9 |

| [9] |

YU T S, LUE W L, WANG S M, et al. Mutation of Arabidopsis plastid phosphoglucose isomerase affects leaf starch synthesis and floral initiation[J]. Plant Physiol, 2000, 123(1): 319-326. DOI:10.1104/pp.123.1.319 |

| [10] |

ZHANG Y Y, FANG Z Q. Effect of PGK1 silencing on the proli-feration of SMMC 7721 hepatoma cells[J]. Chin J Integr Trad West Med Liver Dis, 2017, 27(4): 231-233. (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-0264.2017.03.013 |

| [11] |

ZHAO Y, ZHENG Y B, YAN X F, et al. Screening crucial genes for glucose metabolism in rheumatoid arthritis[J]. J Shandong Univ (Health Sci), 2016, 54(3): 30-35, 40. (in Chinese). DOI:10.6040/j.issn.1671-7554.0.2015.842 |

| [12] |

WU D, SUN L, LI C H, et al. Significance of antibodies to the citrullinated glucose-6-phosphate isomerase peptides in rheumatoid arthritis[J]. J Peking Univ (Health Sci), 2016, 48(6): 937-941. (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-167X.2016.06.003 |

| [13] |

ROSA-TÉLLEZ S, ANOMAN A D, FLORES-TORNERO M, et al. Phosphoglycerate kinases are co-regulated to adjust metabolism and to optimize growth[J]. Plant Physiol, 2018, 176(2): 1182-1198. DOI:10.1104/pp.17.01227 |

| [14] |

HUANG S X, SIRIKHACHORNKIT A, FARIS J D, et al. Phylo-genetic analysis of the acetyl-CoA carboxylase and 3-phosphoglycerate kinase loci in wheat and other grasses[J]. Plant Mol Biol, 2002, 48(5/6): 805-820. DOI:10.1023/a:1014868320552 |

| [15] |

TRONCOSO-PONCE M A, RIVOAL J, CEJUDO F J, et al. Cloning, biochemical characterisation, tissue localisation and possible posttrans-lational regulatory mechanism of the cytosolic phosphoglucose isomerase from developing sunflower seeds[J]. Planta, 2010, 232(4): 845-859. DOI:10.2307/23391986 |

| [16] |

TRONCOSO-PONCE M A, KRUGER N J, RATCLIFFE G, et al. Characterization of glycolytic initial metabolites and enzyme activities in developing sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) seeds[J]. Phytoche-mistry, 2009, 70(9): 1117-1122. DOI:10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.07.012 |

| [17] |

ZHU P H, MA Y Y, ZHU L Z, et al. Selection of suitable reference genes in Pinus massoniana Lamb. under different abiotic stresses for qPCR normalization[J]. Forests, 2019, 10(8): 632. DOI:10.3390/f10080632 |

| [18] |

HUANG X Z, ZHAO Y C. Functional analysis of PGK gene family in Arabidopsis[J]. J Mount Agric Biol, 2017, 36(1): 12-17, 35. (in Chinese). DOI:10.15958/j.cnki.sdnyswxb.2017.01.002 |

| [19] |

GUO N, ZHAO J H, GAO T S, et al. Cloning and expression analysis of PGK gene in Brassica napus[J]. Acta Bot Boreali-Occid Sin, 2014, 34(11): 2188-2193. (in Chinese). DOI:10.7606/j.issn.1000-4025.2014.11.2188 |

| [20] |

XU Y, CHEN J H, ZHU A G, et al. Research progress on response mechanism of plant under low temperature stress[J]. Plant Fiber Sci China, 2015, 37(1): 40-49. (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0517-6611.2016.33.006 |

| [21] |

WANG F, WANG Q, ZHAO X Y. Research progress of phenotype and physiological response mechanism of plants under low temperature stress[J]. Mol Plant Breed, 2019, 17(15): 5144-5153. (in Chinese). DOI:10.13271/j.mpb.017.005144 |

| [22] |

JIANG Z S, SUN X Q, AI X Z, et al. Responses of Rubisco and Rubisco activase in cucumber seedlings to low temperature and weak light[J]. Chin J Appl Ecol, 2010, 21(8): 2045-2050. (in Chinese). DOI:10.13287/j.1001-9332.2010.0300 |

| [23] |

ZENG Y, YU J, CANG J, et al. Detection of sugar accumulation and expression levels of correlative key enzymes in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum) at low temperatures[J]. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem, 2011, 75(4): 681-687. DOI:10.1271/bbb.100813 |

| [24] |

CHEN H. Genetic relationships analysis of longan germplasm resources and studies on low temperature resistance of 'Shixia' Longan seedlings[D]. Nanning: Guangxi University, 2012: 90-92. (in Chinese)

|

| [25] |

VAN HEERDEN P D R, KRÜGER G H J, LOVELAND J E, et al. Dark chilling imposes metabolic restrictions on photosynthesis in soybean[J]. Plant Cell Environ, 2003, 26(2): 323-337. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-3040.2003.00966.x |

| [26] |

SUN Y M, LIU L J, FENG M F, et al. Research progress of sugar metabolism of plants under cold stress[J]. J NE Agric Univ, 2015, 46(7): 95-102, 108. (in Chinese). DOI:10.19720/j.cnki.issn.1005-9369.2015.07.015 |

| [27] |

WU F, SUN X B, ZOU B Z, et al. Transcriptional analysis of Masson pine (Pinus massoniana) under high CO2 stress[J]. Genes (Basel), 2019, 10(10): 804. DOI:10.3390/genes10100804 |

| [28] |

DRAKE B G, GONZÀLEZ-MELER M A, LONG S P. More efficient plants: A consequence of rising atmospheric CO2[J]. Annu Rev Plant Phys Plant Mol Biol, 1997, 48(1): 609-639. DOI:10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.609 |

| [29] |

MOORE B D, CHENG S H, SIMS D, et al. The biochemical and molecular basis for photosynthetic acclimation to elevated atmospheric CO2[J]. Plant Cell Environ, 1999, 22(6): 567-582. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-3040.1999.00432.x |

| [30] |

TURNBULL M H, TISSUE D T, GRIFFIN K L, et al. Photosynthetic acclimation to long-term exposure to elevated CO2 concentration in Pinus radiata D. Don. is related to age of needles[J]. Plant Cell Environ, 1998, 21(10): 1019-1028. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-3040.1998.00374.x |

2021, Vol. 29

2021, Vol. 29