植物的生长发育被认为是一系列可识别的变化事件综合的结果,导致植株的结构发生量变和质变的过程,如根的生长、叶的发育、花形态的建成、胚胎的发育和种子的形成等[1]。从发育生物学的角度来讲,生长发育是生命现象的发展和延伸,是生物有机体自我构建和自我组织的必然过程[2]。植物的生长和发育是不可分离的生命过程。植物的生长伴随着细胞的膨大,数目增多,体积增长,是一个不可逆的过程。在植物生长的同时,发育也同时进行,从胚胎发育到植株衰退,遵循生命周期,完成个体的发育[3]。植物的生长发育是一个复杂的调控过程,由基因的精细表达和外在的环境因素共同调控。近年来,已报道大量与植物生长发育相关的蛋白,如拟南芥(Arabidopsis thaliana)的WHY蛋白(whirly1),可以通过维持细胞器基因组的稳定、抗病信号的转导调节植物叶片的衰老[4];高等植物CYCD3蛋白(cyclin D3)可以影响植物根的二级生长[5];植物中钙依赖蛋白激酶(Ca/calmodulin- dependent protein kinases, CDPK)在花粉管的伸长和胁迫反应中起重要作用[6];此外还有其他蛋白也参与调控植物生长发育的过程[7-10]。随着测序技术的发展,许多新的基因不断被报道和研究。

编码PPR蛋白的基因是2000年通过测序技术被报道且命名的,因其蛋白基序结构与TPR基序结构相似,均含有三角状五肽重复的序列而被命名为PPR (pentatricopeptide repeat)[11]。目前的研究表明PPR家族大量存在于陆生植物中,在拟南芥和水稻(Oryza sativa)基因组中均有超过400个成员[12-13]。在玉米(Zea mays)、油菜(Brassica napus)和番茄(Lycopersicon esculentum)等植物中也相继报道了PPR家族的存在[14-16]。PPR作为一类反式作用因子,主要涉及RNA的转录后修饰,从而调控植物生长发育相关基因的表达,在植物抗逆性和植物生长发育过程等方面起着重要的作用[17-18]。本文对近年来植物PPR蛋白的分类、定位、RNA修饰的机制及其对植物生长发育的影响进行综述,并对植物PPR发挥功能区域和参与的调控网络的研究进行了展望。

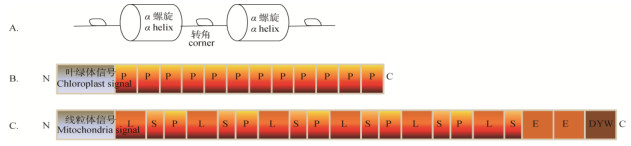

1 PPR蛋白家族的分类和定位 1.1 分类PPR蛋白一般包含2~27个串联重复的结构域, 每个结构域有31~36个氨基酸残基。利用计算机软件预测PPR的基序结构并进行分类,根据基序类型PPR主要可分为两个亚家族[12](图 1)。经典的PPR基序由串联重复的35个氨基酸排列形成,称为P模型(图 1: B)。在此基础上又延伸出含有36个氨基酸残基的L模型,以及含有31个氨基酸残基的S模型[19]。均由经典的P模型组成的PPR蛋白称为P亚家族[20],如水稻中的WSL4 (white stripe leaf 4)就属于这一亚家族的成员[21];由经典P模型、L模型和S模型交替排列的为PLS亚家族(图 1: C),如拟南芥GRS1蛋白(growing slowly 1),参与RNA的编辑和植物的发育[15, 22]。再根据羧基端结构域的不同,还可对PLS亚家族进一步划分。PPR蛋白每个重复基序通常会形成1个稳定的α螺旋-转角-α螺旋结构[20](图 1: A)。还可以再进一步折叠形成超螺旋结构,与相关蛋白发生互作;同时PPR还能够结合在单链RNA上,对靶基因的转录本进行剪接及编辑,进而影响植物的生长发育[23-24]。拟南芥中的MTL1蛋白(mitochondrial translation factor1)可以剪接线粒体NADH脱氢酶7基因的转录本[25];MORF9蛋白(multiple organellar RNA editing factor 9)与PLS类PPR蛋白共同作用在RNA编辑过程中,可以提高RNA编辑的效率[26]; CLB19 (chloroplast biogenesis 19)与MORF2相互作用,共同编辑RNA,clb19突变体会使植物雌配子体不正常发育,植物的生长发育呈现异常现象[27]。

|

图 1 PPR蛋白基序结构(A)和两大亚家族(B, C)[22] Fig. 1 PPR proteins motif structure (A) and two subfamilies (B, C)[22] |

大多数PPR蛋白氨基端具有定位信号序列[28]。多数PPR蛋白主要定位在细胞内的线粒体或叶绿体上,如拟南芥OTP43蛋白(organelle transcript pro- cessing 43)定位在线粒体上,参与NAD1基因内含子的剪接[29];OTP70 (organelle transcript processing 70)则定位在叶绿体上[30]。有少数PPR蛋白存在双定位模式,如水稻OsPGL1蛋白(pale green leaf1)同时定位在叶绿体和线粒体上[31],而拟南芥PNM1蛋白则同时定位于细胞核及线粒体上[32]。

2 PPR蛋白参与植物生长发育与胁迫反应的调节 2.1 PPR蛋白调节植物种子的发育研究表明,PPR蛋白在种子发育过程中具有重要的调控作用。拟南芥GRP23基因(glutamine-rich protein 23)单插入杂合突变体的种子中,有四分之一的胚胎致死,认为缺失GRP23会造成胚胎发育受阻[33]。大多数的grp23突变体胚胎受阻发生在16细胞球形胚时期之前,并且有19%细胞分裂畸形。GRP23主要在胚胎发育时期表达且GRP23定位在根的细胞核中,可以与RNA聚合酶Ⅱ发生互作[33], 还与植物下胚轴的分化相关[34]。玉米谷粒缺陷型植株虽然可以长出谷粒,但为营养不良型小谷粒,是延迟植物发育的经典类型。研究表明,DEK2 (defective kernel 2)和DEK10基因在玉米中分别编码PPR家族中的1个成员,其中DEK2主要参与玉米线粒体转录本的剪接[35],而DEK10则是通过编辑线粒体转录本从而影响玉米细胞线粒体的功能[36]。dek2和dek10突变体均能产生胚乳发育不全、小而有缺陷的谷粒[35-36]。最新的研究表明,dek37突变体玉米中胚乳和胚芽的发育有明显缺陷,后来证实DEK37蛋白(defective kernel 37)可以影响线粒体中第二类内含子的剪接和玉米种子的正常发育[37]。除以上基因,EMP11 (empty pericarp 11)和EMP16基因突变也会导致玉米种子发育异常,EMP16蛋白主要参与对线粒体NAD2内含子4的剪接,EMP11蛋白则是剪接NAD1的内含子,他们的基因突变均能导致种子发育不良,甚至造成空谷粒的现象[38-39]。这些表明PPR家族蛋白在植物种子发育的过程中起到重要的调节作用。

2.2 PPR蛋白参与指导胞质雄性不育的育性恢复细胞质雄性不育是广泛存在于高等植物中的一种自然现象,表现为母体遗传、花粉败育和雌蕊正常[40]。在研究水稻细胞质雄性不育的过程中,RF基因(fertility restorer)被认为是一类育性恢复基因[41]。曾有报道水稻中RF4、RF1A和RF1B基因为育性恢复基因且均编码PPR蛋白[42-43]。并且,这3个基因编码的蛋白以线粒体为目标,通过剪切和降解机制来阻碍线粒体ORF79蛋白(open reading frame 79)的累积,从而恢复水稻的育性[43]。水稻中RF98基因也可恢复细胞质雄性不育,距离RF98基因170 kb的PPR762基因编码1个PPR家族成员,PPR762指导恢复RT98类型水稻的部分雄性不育性状,使结实率达到9.3%[44]。推测RF98基因在恢复水稻细胞质雄性不育中除需要PPR762基因的参与,可能还需要RF98基因周围区域其他基因的共同参与才能完全恢复水稻中RT98类型的雄性不育性状[44]。除了上述PPR蛋白可以指导雄性不育的育性恢复,水稻中其他PPR蛋白也有相似的功能,如RF6、PPR592和PPR676等[45-47]。此外,欧洲的1个油菜品系中有1个定位在线粒体上的RFn蛋白可以恢复胞质雄性不育,RFn基因(fertility restorer nap)编码1个PPR蛋白[14]。通过对棉花(Gossypium spp.)进行全基因组分析表明,棉花中多数PLS亚族的PPR蛋白与胞质雄性不育和恢复相关[48]。

2.3 PPR蛋白参与调控叶绿体的形成、叶的发育和根的生长 2.3.1 参与调控叶绿体的形成叶绿体的主要作用是进行光合作用并合成植物生长所需的相关物质。目前关于叶绿体的形成机制仍然处于比较模糊的状态。全基因组分析拟南芥中的PPR家族,表明他们在叶绿体的形成中起着不可或缺的作用[49]。PPR家族中的THA8蛋白(thylakoid assembly 8)在剪接被子植物叶绿体编码基因的第二类内含子中是必不可少的。玉米tha8突变体中,幼苗期类囊体蛋白和色素均受损,叶绿体形成不完善导致叶片颜色呈浅绿色[50]。玉米PPR4参与叶绿体RPS12 (ribosomal protein s12)前体RNA内含子1的反式剪接,敲除该基因会使质体核糖体无法正常积累,导致玉米幼苗叶片黄化和白化[51]。拟南芥OTP51 (organelle transcript processing 51)参与质体YCF3基因(hypothetical chloroplast open reading frame 3)内含子2的顺式剪接等,OTP51突变影响光系统Ⅰ和光系统Ⅱ的组装,表现为叶绿体形成异常,植株叶片白化[52]。拟南芥ECB2蛋白(early chloroplast development 2)可以编辑质体ACCD基因(acetyl coA carboxylase subunit D)和NDHF基因(nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase subunit F)的转录本,ECB2基因突变会使植株出现白化和败育性状,突变体中ACCD和NDHF基因的编辑效率受到影响,且突变体叶片相对于野生型表现出延迟绿化表型[53]。广泛筛选拟南芥叶片颜色异常突变体,找到1个定位于叶绿体且编码PPR蛋白的WTG1基因(white to green 1),敲除该基因会影响叶绿体的发育,阻碍叶片的早期绿化,光合作用不能正常进行,植株的生长受到抑制;恢复WTG1基因的表达则能使突变体恢复正常表型[54]。ECD1 (early chloroplast development 1)编码1个定位于叶绿体上的PPR蛋白,敲除ECD1会导致胚胎致死或不正常的胚胎发育[55]。利用RNAi技术使ECD1基因的表达减少,幼苗子叶出现白化但叶片形态正常, 这种异常现象是叶绿体类囊体膜系统发育延迟引起的,认为ECD1是一个可以编辑RPS14基因转录本的转录因子以及调节叶绿体早期发育的蛋白[55]。除以上PPR蛋白外,水稻PPR6[56]、拟南芥SOT5 (suppressor of thylakoid formation 5)[57]、SOT1 (suppressor of thyla- koid formation 1)[58]和PDM1 (pigment deficient mutant 1)[59]也参与叶绿体的形成和调控相关基因的表达。

2.3.2 参与叶的发育PPR蛋白在调控植物叶绿体的形成时,也会影响叶的发育。在植物生长发育过程中PPR家族对叶的发育起着不可或缺的作用。拟南芥OTP70是一个E类的PPR蛋白,缺失该蛋白会使RPOC1基因(RNA polymerase beta’ chain 1)转录本剪接受损,叶片呈淡黄色,整体植株发育不良,较野生型更为矮小[30]。水稻WSL4基因在叶片发育早期,影响叶绿体的生成;wsl4突变体叶片出现白色条纹,叶绿素含量比野生型少,但叶片大小和植株生长没有受到明显的影响[20]。拟南芥PPR596是一个P亚族的PPR蛋白, 可以编辑线粒体的转录本,ppr596突变体和野生型的叶片颜色无明显区别,但生长早期的ppr596突变体的叶片更小,突变体植株也比野生型小得多;到生长后期,ppr596突变体和野生型植株大小无明显差异,但ppr596突变体叶片更为卷曲,呈不规则形状[60]。PPR蛋白不仅与叶片的大小和形态建成相关,还与叶片衰老有一定的关系。拟南芥中的1个PPRs基因在某种程度上参与了一些衰老外源因素的诱导,从而负调控拟南芥叶片的衰老进程[61]。

2.3.3 调节根的生长根作为植物的营养器官,通常位于地表以下, 负责吸收和运输水分及溶解于其中的无机盐,并且具有支持、合成和贮存有机物质的作用[62]。PPR蛋白除调控植物叶片发育外还影响根的生长。拟南芥SLO3蛋白定位在线粒体上,参与NADH脱氢酶亚基7编码基因内含子2的剪接;缺失该蛋白导致植物存在发育缺陷,种子萌发延缓、根的长度较野生型显著缩短、叶片卷曲,抽苔迟缓等[63]。SLO3还与植物生长素信号通路作用相关,调节根尖分生组织的活性范围[64]。同时,拟南芥中的SLO4蛋白涉及NAD4基因的编辑和NAD2内含子1的剪接,slo4突变体根的长度较野生型显著缩短,影响植株的整体发育[65]。拟南芥SLG1蛋白影响线粒体RNA的编辑和植物发育,与野生型相比,slg1突变体的根较短, 根尖分生组织较短且侧根少,对ABA、NaCl和甘露醇更加敏感,且更耐受干旱胁迫[66]。

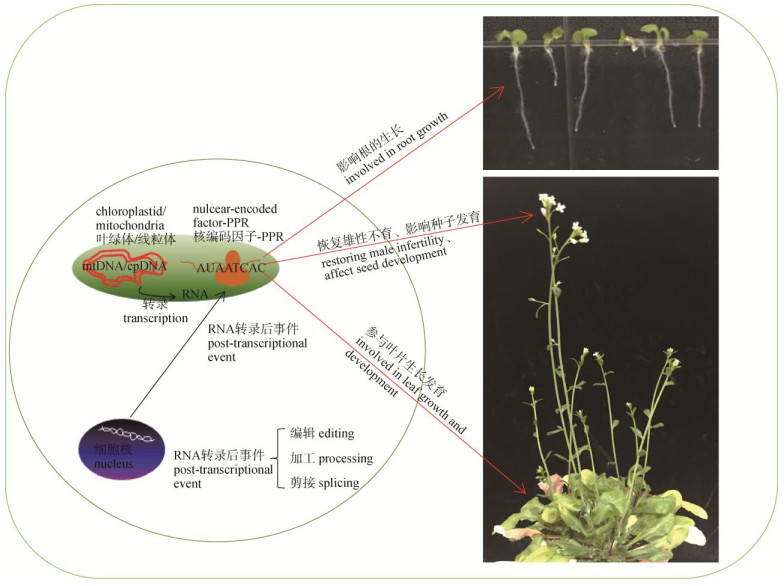

综上所述,PPR蛋白可以通过剪接和编辑相关基因的转录本,影响这些目标基因的功能,从而参与叶和根的生长发育最终调控植物的生长(图 2)。

|

图 2 PPR蛋白参与调控植物生长发育 Fig. 2 Regulation of plant growth and development by PPR proteins |

植物生长过程中会受到许多逆境因素的影响。近年来的研究表明PPR蛋白参与响应胁迫反应的功能[13, 67-70]。拟南芥中WSL蛋白(white stripe leaf)在参与RPL2基因(ribosomal protein L2)转录本剪接效率的同时,还响应胁迫反应;wsl突变体相对于野生型对脱落酸、盐和糖更加敏感,可以积累更多的过氧化氢[13]。拟南芥PPR96参与调节植株盐、脱落酸和氧化应激反应,ppr96突变体对盐、脱落酸和氧化应激均不敏感[71]。SOAR1基因(suppressor of the ABAR overexpressor 1)的表达下调会使植株对脱落酸反应敏感,上调表达则相反,说明SOAR1基因在脱落酸信号通路中起负调控作用[72]。进一步研究表明,过表达SOAR1可以增强植株对干旱、冷和盐的耐受力[73]。运用计算机软件从欧洲大叶杨(Populus lasiocarpa)的全基因组中找到154个与胁迫相关的PPR基因,冷处理时,大叶杨PPR5基因的表达显著上调;盐处理时,PPR5、PPR277和PPR574的表达水平显著上调;茉莉酸甲酯处理时,PPR28基因的表达水平显著上调[70]。这表明PPR基因家族能够响应植物生长发育过程不同的胁迫反应[13, 70]。

3 PPR蛋白的作用机制PPR家族作为一类反式作用因子参与基因的表达调控,主要是在转录后水平的RNA修饰中发挥作用[15, 74-75]。目前的研究表明,PPR家族对RNA的修饰主要分为以下3种类型,第一种类型为PPR蛋白识别并结合在目标RNA上,阻碍RNA外切酶的活性, 使其形成稳定的单顺反子进行表达[75-76];第二种类型为PPR特异识别RNA编辑的顺式作用元件并招募相关编辑因子共同起作用,把特定的胞嘧啶转变成尿嘧啶或特定的尿嘧啶转变成胞嘧啶,改变氨基酸的序列,创造新的翻译起始位点或者终止位点[23, 55];第三种类型为DNA转录后的前体RNA含有丰富的内含子,需要进行切除然后拼接为成熟RNA。剪接过程中,一般PPR蛋白结合在RNA上,帮助RNA正确折叠形成催化结构,保护活性区域,并辅助RNA酶进行催化[63]。PPR蛋白通过对目的基因的转录本进行修饰,激活或者抑制基因的表达活性,进而调控植物的生长发育[77-78]。

4 展望叶绿体和线粒体是提供植物细胞生长发育所需能量和养分的场所,并且能够感知外界环境信号,调节植物的生长[79]。目前已报道的大多数PPR蛋白都定位于细胞的叶绿体和线粒体上,并且在植物生长发育中的作用也有了一定了解。以往的综述文章主要是针对PPR蛋白的起源、分类定位以及在计算机软件辅助下不断发现新的PPR蛋白,预测和验证功能区域。本文主要描述了PPR蛋白可以对细胞器特异基因的转录本进行修饰和加工,并且以某种方式参与调节植物生长发育和响应胁迫反应(表 1)。但其具体的调控网络和特异性还有待进一步的探究。PPR蛋白在调节植物生长发育是否存在时空性和组织特异性?PPR蛋白在发挥不同功能时,其结构是否发生改变?PPR蛋白是如何特异识别并结合在RNA上的?有文献曾报道,TPR蛋白的氨基端部分与蛋白自身的稳定性、聚化状态以及和其它蛋白之间相互作用的能力密切相关[80-81]。PPR蛋白的结构与TPR蛋白的结构相似[11],其氨基端是否也存在相似的功能还不清楚。另外,以往的研究大多集中在PPR结合的特异RNA上,对与PPR共同作用的蛋白研究较少;对于这些未知的部分还有待于进一步研究。此外,关于PPR的功能研究目前多停留在理论层面,运用到农业生产实践中还相对较少。PPR蛋白可以恢复植物雄性不育性状[48];并能在逆境条件下,提高作物的质量和产量[82]。在农业生产中,是否可以利用相关PPR蛋白的育性恢复机制和抗逆性等功能,培育优良的农作物新品种。要解决这些问题,需要进一步深入研究PPR家族的功能,进一步阐述植物PPR发挥功能区域以及明确参与的调控网络。

| 表 1 参与调节植物生长发育的部分PPR蛋白 Table 1 Some of pentatricopeptide repeat proteins involved in plant growth and development regulation |

| [1] |

BONHOMME R. Bases and limits to using 'degree.day' units[J]. Eur J Agron, 2000, 13(1): 1-10. DOI:10.1016/S1161-0301(00)00058-7 |

| [2] |

TAN D H, LI F H. Introduction to the definition of plant development[J]. Minying Keji, 2017(11): 71-72. 谭大海, 李富恒. 浅谈植物发育的定义[J]. 民营科技, 2017(11): 71-72. |

| [3] |

DAMBREVILLE A, LAURI P ÉE, NORMAND F, et al. Analysing growth and development of plants jointly using developmental growth stages[J]. Ann Bot, 2015, 115(1): 93-105. DOI:10.1093/aob/mcu227 |

| [4] |

LIN W F, REN Y J, MIAO Y. Research progress of whirly proteins in regulation of leaf senescence[J]. J Plant Physiol J, 2014, 20(9): 1274-1284. 林文芳, 任育军, 缪颖. 植物Whirly蛋白调控叶片衰老的研究进展[J]. 植物生理学报, 2014, 20(9): 1274-1284. DOI:10.13592/j.cnki.ppj.2014.1013 |

| [5] |

RANDALL R S, MIYASHIMA S, BLOMSTER T, et al. AINTEGU-MENTA and the D-type cyclin CYCD3;1 regulate root secondary growth and respond to cytokinins[J]. Biol Open, 2015, 4(10): 1229-1236. DOI:10.1242/bio.013128 |

| [6] |

WU Z G, WU S J, WANG Y C, et al. Advances in studies of calcium- dependent protein kinase (CDPK) in plants[J]. Acta Pratacult Sci, 2018, 27(1): 204-214. 武志刚, 武舒佳, 王迎春, 等. 植物中钙依赖蛋白激酶(CDPK)的研究进展[J]. 草业学报, 2018, 27(1): 204-214. DOI:10.11686/cyxb2017211 |

| [7] |

NIU Y L, JIANG X M, XU X Y. Reaserch advances on transcription factor MYB gene family in plants[J]. Mol Plant Breed, 2016, 14(8): 2050-2059. 牛义岭, 姜秀明, 许向阳. 植物转录因子MYB基因家族的研究进展[J]. 分子植物育种, 2016, 14(8): 2050-2059. DOI:10.13271/j.mpb.014.002050 |

| [8] |

TAO J H, LIANG W Q, AN G, et al. OsMADS6 controls flower development by activating rice factor of DNA methylation like1[J]. Plant Physiol, 2018, 177(2): 713-727. DOI:10.1104/pp.18.00017 |

| [9] |

TAN X L, FAN Z Q, SHAN W, et al. Association of BrERF72 with methyl jasmonate-induced leaf senescence of Chinese flowering cabbage through activating JA biosynthesis-related genes[J]. Hort Res, 2018, 5: 22. DOI:10.1038/s41438-018-0028-z |

| [10] |

ZHANG T T, TIAN Y, LU X Y. The regulatory role of WRKY trans-cription factors in plant growth and development[J]. Chem Bioeng, 2014, 31(8): 1-5. 张婷婷, 田云, 卢向阳. WRKY转录因子在植物生长发育中的调控作用[J]. 化学与生物工程, 2014, 31(8): 1-5. DOI:10.3969/J.ISSN.1672-5425.2014.08.001 |

| [11] |

SMALL I D, PEETERS N. The PPR motif:A TPR-related motif prevalent in plant organellar proteins[J]. Trends Biochem Sci, 2000, 25(2): 46-47. |

| [12] |

RIVALS E, BRUYÈERE C, TOFFANO-NIOCHE C, et al. Formation of the Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat family[J]. Plant Physiol, 2006, 141(3): 825-839. DOI:10.1104/pp.106.077826 |

| [13] |

TAN J J, TAN Z H, WU F Q, et al. A novel chloroplast-localized pentatricopeptide repeat protein involved in splicing affects chloroplast development and abiotic stress response in rice[J]. Mol Plant, 2014, 7(8): 1329-1349. DOI:10.1093/mp/ssu054 |

| [14] |

LIU Z, DONG F M, WANG X, et al. A pentatricopeptide repeat protein restores nap cytoplasmic male sterility in Brassica napus[J]. J Exp Bot, 2017, 68(15): 4115-4123. DOI:10.1093/jxb/erx239 |

| [15] |

BARKAN A, SMALL I. Pentatricopeptide repeat proteins in plants[J]. Annu Rev Plant Biol, 2013, 65(1): 415-442. DOI:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040159 |

| [16] |

DING A M, QU X, LI L, et al. Genome-wide identification and bioinformatic analysis of PPR gene family in tomato[J]. Hereditas, 2014, 36(1): 77-84. 丁安明, 李凌, 屈旭, 等. 番茄PPR基因家族的鉴定与生物信息学分析[J]. 遗传, 2014, 36(1): 77-84. DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1005.2014.0085 |

| [17] |

DING A M, QU X, LI L, et al. The progress of PPR protein family in plants[J]. Chin Agric Sci Bull, 2014, 30(9): 218-224. 丁安明, 屈旭, 李凌, 等. 植物PPR蛋白家族研究进展[J]. 中国农学通报, 2014, 30(09): 218-224. |

| [18] |

ICHINOSE M, SUGITA M. RNA editing and its molecular mechanism in plant organelles[J]. Genes (Basel), 2016, 8(1): E5. DOI:10.3390/genes8010005 |

| [19] |

O'TOOLE N, HATTORI M, ANDRES C, et al. On the expansion of the pentatricopeptide repeat gene family in plants[J]. Mol Biol Evol, 2008, 25(6): 1120-1128. DOI:10.1093/molbev/msn057 |

| [20] |

LI Q X. Structural and biochemical study of PPR proteinsStructural biology and biochemistry of PPR protein[D]. Beijing: Tsinghua University, 2015. 李泉秀. PPR蛋白的结构生物学和生物化学研究[D].北京: 清华大学, 2015. |

| [21] |

WANG Y, RRE Y L, ZHOU K N, et al. White stripe leaf4 encodes a novel P-type PPR protein required for chloroplast biogenesis during early leaf development[J]. Front Plant Sci, 2017, 8: 1116. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2017.01116 |

| [22] |

XIE T T, CHEN D, WU J, et al. Growing slowly 1 locus encodes a PLS-type PPR protein required for RNA editing and plant development in Arabidopsis[J]. J Exp Bot, 2016, 67(19): 5687-5698. DOI:10.1093/jxb/erw331 |

| [23] |

WAGONER J, SUN T, LIN L, et al. Cytidine deaminase motifs within the DYW domain of two pentatricopeptide repeat-containing proteins are required for site-specific chloroplast RNA editing[J]. J Biol Chem, 2015, 290(5): 2957-2968. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M114.622084 |

| [24] |

HEIN A, POLSAKIEWICZ M, KNOOP V. Frequent chloroplast RNA editing in early-branching flowering plants:Pilot studies on angiosperm- wide coexistence of editing sites and their nuclear specificity factors[J]. BMC Evol Biol, 2016, 16: 23. DOI:10.1186/s12862-016-0589-0 |

| [25] |

HAILI N, PLANCHARD N, ARNAL N, et al. The MTL1 pentatrico- peptide repeat protein is required for both translation and splicing of the mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase subunit7 mRNA in Arabidopsis[J]. Plant Physiol, 2016, 170(1): 354-366. DOI:10.1104/pp.15.01591 |

| [26] |

YAN J J, ZHANG Q X, GUAN Z Y, et al. MORF9 increases the RNA- binding activity of PLS-type pentatricopeptide repeat protein in plastid RNA editing[J]. Nat Plants, 2017, 3(5): 17037. DOI:10.1038/nplants.2017.37 |

| [27] |

RAMOS-VAEG M, GUEVARA-GARCÍA A, LLAMAS E, et al. Func- tional analysis of the Arabidopsis thaliana chloroplast biogenesis 19 pentatricopeptide repeat editing protein[J]. New Phytol, 2015, 208(2): 430-441. DOI:10.1111/nph.13468 |

| [28] |

EMANUELSSON O, NIELSEN H, BRUNAK S, et al. Predicting sub- cellular localization of proteins based on their N-terminal amino acid sequence[J]. J Mol Biol, 2000, 300(4): 1005-1016. DOI:10.1006/jmbi.2000.3903 |

| [29] |

de LONGEVIALLE A F, MEYER E H, ANDRÉES C, et al. The penta- tricopeptide repeat gene OTP43 is required for trans-splicing of the mitochondrial nad1 intron 1 in Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Plant Cell, 2007, 19(10): 3256-3265. DOI:10.1105/tpc.107.054841 |

| [30] |

CHATEIGNER-BOUTIN A L, des FRANCS-SMALLl C, DELANNOY E, et al. OTP70 is a pentatricopeptide repeat protein of the E subgroup involved in splicing of the plastid transcript rpoC1[J]. Plant J, 2011, 65(4): 532-542. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04441.x |

| [31] |

XIAO H J, XU Y H, NI C Z, et al. A rice dual-localized pentatri- copeptide repeat protein is involved in organellar RNA editing together with OsMORFs[J]. J Exp Bot, 2018, 69(12): 2923-2936. DOI:10.1093/jxb/ery108 |

| [32] |

HAMMANT K, GOBERT A, HLEIBIEH K, et al. An Arabidopsis dual-localized pentatricopeptide repeat protein interacts with nuclear proteins involved in gene expression regulation[J]. Plant Cell, 2011, 23(2): 730-740. DOI:10.1105/tpc.110.081638 |

| [33] |

DING Y H, LIU N Y, TANG Z S, et al. Arabidopsis glutamine-rich protein23 is essential for early embryogenesis and encodes a novel nuclear PPR motif protein that interacts with RNA polymerase Ⅱ subunit Ⅲ[J]. Plant Cell, 2006, 18(4): 815-830. DOI:10.1105/tpc.105.039495 |

| [34] |

ZHANG D J, WANG X M, WANG M, et al. Ectopic expression of WUS in hypocotyl promotes cell division via grp23 in Arabidopsis[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(9): e75773. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0075773 |

| [35] |

QI W W, YANG Y, FENG X Z, et al. Mitochondrial function and maize kernel development requires dek2, a pentatricopeptide repeat protein involved in nad1 mRNA splicing[J]. Genetics, 2017, 205(1): 239-249. DOI:10.1534/genetics.116.196105 |

| [36] |

QI W W, TIAN Z R, LU L, et al. Editing of mitochondrial transcripts nad3 and cox2 by dek10 is essential for mitochondrial function and maize plant development[J]. Genetics, 2017, 205(4): 1489-1501. DOI:10.1534/genetics.116.199331 |

| [37] |

DAI D W, LUAN S C, CHEN X Z, ZWANG Q, et al. Maize dek37 encodes a P-type PPR protein that affects cis-splicing of mitochondrial nad2 intron 1 and seed development[J]. Genetics, 2018, 208(3): 1069-1082. DOI:10.1534/genetics.117.300602 |

| [38] |

XIU Z H, SUN F, SHEN Y, et al. Empty pericarp16 is required for mitochondrial nad2 intron 4cis-splicing, complex Ⅰ assembly and seed development in maize[J]. Plant J, 2016, 85(4): 507-519. DOI:10.1111/tpj.13122 |

| [39] |

REN X M, PAN Z Y, ZHAO H L, et al. Empty pericarp 11 serves as a factor for splicing of mitochondrial nad1 intron and is required to ensure proper seed development in maize[J]. J Exp Bot, 2017, 68(16): 4571-4581. DOI:10.1093/jxb/erx212 |

| [40] |

LING X Y, ZHOU P J, ZHU Y G. Progress of the studies on molecular machanism of cytoplasmic male sterilityin the mechanism of cytoplasmic male sterility in plants[J]. Chin Bull Bot, 2000, 17(4): 319-332. 凌杏元, 周培疆, 朱英国. 植物细胞质雄性不育分子机理研究进展[J]. 植物学报, 2000, 17(4): 319-332. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-3466.2000.04.005 |

| [41] |

KAZAMA T, TORIYAAMA K. A fertility restorer gene, Rf4, widely used for hybrid rice breeding encodes a pentatricopeptide repeat protein[J]. Rice, 2014, 7(1): 28. DOI:10.1186/s12284-014-0028-z |

| [42] |

TANG H W, LUO D P, ZHOU D G, et al. The rice restorer Rf4 for wild-abortive cytoplasmic male sterility encodes a mitochondrial- localized PPR protein that functions in reduction of WA352 transcripts[J]. Mol Plant, 2014, 7(9): 1497-1500. DOI:10.1093/mp/ssu047 |

| [43] |

WANG Z H, ZOU Y J, LI X Y, et al. Cytoplasmic male sterility of rice with Boro Ⅱ cytoplasm is caused by a cytotoxic peptide and is restored by two related PPR motif genes via distinct modes of mRNA silencing[J]. Plant Cell, 2006, 18(3): 676-687. DOI:10.1105/tpc.105.038240 |

| [44] |

IGARASHI K, KAZAMA T, TORIYAMA K. A gene encoding pentatri- copeptide repeat protein partially restores fertility in rt98-type cytoplasmic male-sterile rice[J]. Plant Cell Physiol, 2016, 57(10): 2187-2193. DOI:10.1093/pcp/pcw135 |

| [45] |

GABORIEAU L, BROWN G G, MIREAU H. The propensity of pentatricopeptide repeat genes to evolve into restorers of cytoplasmic male sterility[J]. Front Plant Sci, 2016, 7: 1816. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2016.01816 |

| [46] |

HUANG W C, YU C C, HU J, et al. Pentatricopeptide-repeat family protein rf6 functions with hexokinase 6 to rescue rice cytoplasmic male sterility[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2015, 112(48): 14984-14989. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1511748112 |

| [47] |

LIU Y J, LIU X J, CHEN H, et al. A plastid-localized pentatricopeptide repeat protein is required for both pollen development and plant growth in rice[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7(1): 11484. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-10727-x |

| [48] |

ZHANG B, LIU G, LI X, et al. A genome-wide identification and analysis of the DYW-deaminase genes in the pentatricopeptide repeat gene family in cotton (Gossypium spp.)[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(3): e174201. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0174201 |

| [49] |

LURIN C, ANDRÉES C, AUBOURG S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat proteins reveals their essential role in organelle biogenesis[J]. Plant Cell, 2004, 16(8): 2089-2103. DOI:10.1105/tpc.104.022236 |

| [50] |

KHROUCHTCHOVA A, MONDE R, BARKAN A. A short PPR protein required for the splicing of specific group Ⅱ introns in angiosperm chloroplasts[J]. RNA, 2015, 18(6): 1197-1209. DOI:10.1261/rna.032623.112 |

| [51] |

SCHMITZ-LINNEWEBER C, WILLIAMS-CARRIER R, WILLIAMS-VOELKER P, et al. A pentatricopeptide repeat protein facilitates the trans-splicing of the maize chloroplast rps12 pre-mRNA[J]. Plant Cell, 2006, 18(10): 2650-2663. DOI:10.1105/tpc.106.046110 |

| [52] |

de LONGEVIALLE A F, HENDRICKSON L, TAYLOR N L, et al. The pentatricopeptide repeat gene otp51 with two laglidadg motifs is required for the cis-splicing of plastid ycf3 intron 2 in Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Plant J, 2008, 56(1): 157-168. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03581.x |

| [53] |

CAO Z L, YU Q B, SUN Y, et al. A point mutation in the pentatri-copeptide repeat motif of the AtECB2 protein causes delayed chloroplast development[J]. J Integr Plant Biol, 2011, 53(4): 258-269. DOI:10.1111/j.1744-7909.2011.01030.x |

| [54] |

MA F, HU Y C, JU Y, et al. A novel tetratricopeptide repeat protein, white to green1, is required for early chloroplast development and affects RNA editing in chloroplasts[J]. J Exp Bot, 2017, 68(21/22): 5829-5843. DOI:10.1093/jxb/erx383 |

| [55] |

JIANG T, ZHANG J, RONG L W, et al. ECD1 functions as an RNA editing trans-factor of rps14-149 in plastids and is required for early chloroplast development in seedlings[J]. J Exp Bot, 2018, 69(12): 3037-3051. DOI:10.1093/jxb/ery139 |

| [56] |

TANG J P, ZHANG W W, WEN K, et al. OsPPR6, a pentatricopeptide repeat protein involved in editing and splicing chloroplast RNA, is required for chloroplast biogenesis in rice[J]. Plant Mol Biol, 2017, 95(4/5): 345-357. DOI:10.1007/s11103-017-0654-0 |

| [57] |

HUANG W H, ZHU Y J, WU W J, et al. The pentatricopeptide repeat protein sot5/emb2279 is required for plastid rpl2 and trnK intron splicing[J]. Plant Physiol, 2018, 177(2): 684-697. DOI:10.1104/pp.18.00406 |

| [58] |

WU W J, LIU S, RUWE H, et al. SOT1, a pentatricopeptide repeat protein with a small muts-related domain, is required for correct processing of plastid 23S-4.5S rRNA precursors in Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Plant J, 2016, 85(5): 607-621. DOI:10.1111/tpj.13126 |

| [59] |

ZHANG H D. Arabidopsis PPR protein PDM1 is involved directly in splicing and editing of chloroplast RNA[D]. Shanghai: Shanghai Normal University, 2015. 张宏道.拟南芥PPR蛋白PDM1直接参与叶绿体RNA的剪接和编辑[D].上海: 上海师范大学, 2015. |

| [60] |

DONIWA Y, UEDA M, UETA M, et al. The involvement of a PPR protein of the P subfamily in partial RNA editing of an Arabidopsis mitochondrial transcript[J]. Gene, 2010, 454(1/2): 39-46. DOI:10.1016/j.gene.2010.01.008 |

| [61] |

ZHU Z H, REN Y J, LI Y Y, et al. Relationship between pentatrico- peptide repeat gene PPRs and rosette leaf senescence in Arabidopsis[J]. J Fujian Agric For Univ (Nat Sci), 2016, 45(3): 282-289. 朱正火, 任育军, 李燕云, 等. 拟南芥PPRs基因与莲座叶衰老之间的关系[J]. 福建农林大学学报(自然科学版), 2016, 45(3): 282-289. DOI:10.13323/j.cnki.j.fafu(nat.sci.).2016.03.008 |

| [62] |

GYSSELS G, POESEN J, BOCHET E, et al. Impact of plant roots on the resistance of soils to erosion by water:A review[J]. Prog Physl Geogr, 2005, 29(2): 189-217. DOI:10.1191/0309133305pp443ra |

| [63] |

HSIEH W Y, LIAO J C, CHANG C Y, et al. The slow growth 3 pentatri- copeptide repeat protein is required for the splicing of mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase subunit7 intron 2 in Arabidopsis[J]. Plant Physiol, 2015, 168(2): 490-501. DOI:10.1104/pp.15.00354 |

| [64] |

HSIEH W Y, LIAO J C, HSIEH M H. Dysfunctional mitochondria regulate the size of root apical meristem and leaf development in Arabidopsis[J]. Plant Signal Behav, 2015, 10(10): e1071002. DOI:10.1080/15592324.2015.1071002 |

| [65] |

WEIßENBERGER S, SOLL J, CARRIE C. The PPR protein slow growth 4 is involved in editing of nad4 and affects the splicing of nad2 intron 1[J]. Plant Mol Biol, 2017, 93(4/5): 355-368. DOI:10.1007/s11103-016-0566-4 |

| [66] |

YUAN H, LIU D. Functional disruption of the pentatricopeptide protein slg1 affects mitochondrial RNA editing, plant development, and responses to abiotic stresses in Arabidopsis[J]. Plant J, 2012, 70(3): 432-444. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04883.x |

| [67] |

DU L, ZHANG J, QU S F, et al. The pentratricopeptide repeat protein pigment-defective mutant2 is involved in the regulation of chloroplast development and chloroplast gene expression in Arabidopsis[J]. Plant Cell Physiol, 2017, 58(4): 747-759. DOI:10.1093/pcp/pcx004 |

| [68] |

LEE K, HAN J H, PARK Y I, et al. The mitochondrial pentatrico- peptide repeat protein PPR19 is involved in the stabilization of NADH dehydrogenase 1 transcripts and is crucial for mitochondrial function and Arabidopsis thaliana development[J]. New Phytol, 2017, 215(1): 202-216. DOI:10.1111/nph.14528 |

| [69] |

GABOTTI D, CAPORALI E, MANZOTTI P, et al. The maize pentatri- copeptide repeat gene empty pericarp4(emp4) is required for proper cellular development in vegetative tissues[J]. Plant Sci, 2014, 223: 25-35. DOI:10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.02.012 |

| [70] |

XING H T, FU X K, YANG C, et al. Genome-wide investigation of pentatricopeptide repeat gene family in poplar and their expression analysis in response to biotic and abiotic stresses[J]. Sci Rep, 2018, 8(1): 2817. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-21269-1 |

| [71] |

LIU J M, ZHAO J Y, LU P P, et al. The E-subgroup pentatricopeptide repeat protein family in Arabidopsis thaliana and confirmation of the responsiveness PPR96 to abiotic stresses[J]. Front Plant Sci, 2016, 7: 1825. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2016.01825 |

| [72] |

MEI C, JIANG S C, LU Y F, et al. Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat protein soar1 plays a critical role in abscisic acid signalling[J]. J Exp Bot, 2014, 65(18): 5317-5330. DOI:10.1093/jxb/eru293 |

| [73] |

JIANG S C, MEI C, LIANG S, et al. Crucial roles of the pentatrico- peptide repeat protein soar1 in Arabidopsis response to drought, salt and cold stresses[J]. Plant Mol Biol, 2015, 88(4/5): 369-385. DOI:10.1007/s11103-015-0327-9 |

| [74] |

SCHMITZ-LINNEWEBER C, SMALL I S. Pentatricopeptide repeat proteins:A socket set for organelle gene expression[J]. Trends Plant Sci, 2008, 13(12): 663-670. DOI:10.1016/j.tplants.2008.10.001 |

| [75] |

PRIKRYL J, ROJAS M, SCHUSTER G, et al. Mechanism of RNA stabilization and translational activation by a pentatricopeptide repeat protein[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2011, 108(1): 415-420. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1012076108 |

| [76] |

PFALZ J, BAYYRAKTAR O, PRIKRYL J, et al. Site-specific binding of a PPR protein defines and stabilizes 5' and 3' mRNA termini in chloroplasts[J]. EMBO J, 2009, 28(14): 2042-2052. DOI:10.1038/emboj.2009.121 |

| [77] |

ZHOU W B, KARCHER D, FISCHER A, et al. Multiple RNA processing defects and impaired chloroplast function in plants deficient in the organellar protein-only RNase P enzyme[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(3): e120533. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0120533 |

| [78] |

SHEN C C, ZHANG D L, GUAN Z Y, et al. Structural basis for specific single-stranded RNA recognition by designer pentatricopeptide repeat proteins[J]. Nat Commun, 2016, 7: 11285. DOI:10.1038/ncomms11285 |

| [79] |

WANG H R, LÜ X QJ, ZHANG Y, et al. Role of extracellular ATP in plant growth, development and stress responses[J]. J Chin Electron Microc Soc, 2017, 36(1): 83-90. 王浩然, 吕雪芹, 张越, 等. eATP在植物生长发育及逆境胁迫中的作用[J]. 电子显微学报, 2017, 36(1): 83-90. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-6281.2017.01.015 |

| [80] |

THEBAULT P, CHIRGADZE D, DOU Z, et al. Structural and functional insights into the role of the N-terminal mps1 TPR domain in the sac (spindle assembly checkpoint)[J]. Biochem J, 2012, 448(3): 321-328. DOI:10.1042/BJ20121448 |

| [81] |

KANG C B, YE H, CHIA J, et al. Functional role of the flexible N-terminal extension of fkbp38 in catalysis[J]. Sci Rep, 2013, 3(43): 2985. DOI:10.1038/srep02985 |

| [82] |

XIONG J, TAO T, LUO Z, et al. RNA editing responses to oxidative stress between a wild abortive type male-sterile line and its maintainer line[J]. Front Plant Sci, 2017(8): 2023. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2017.02023 |

2019, Vol. 27

2019, Vol. 27